This was originally posted in the SMU CERN blog (http://blog.smu.edu/smucern). It’s reproduced here because I am the author! 🙂

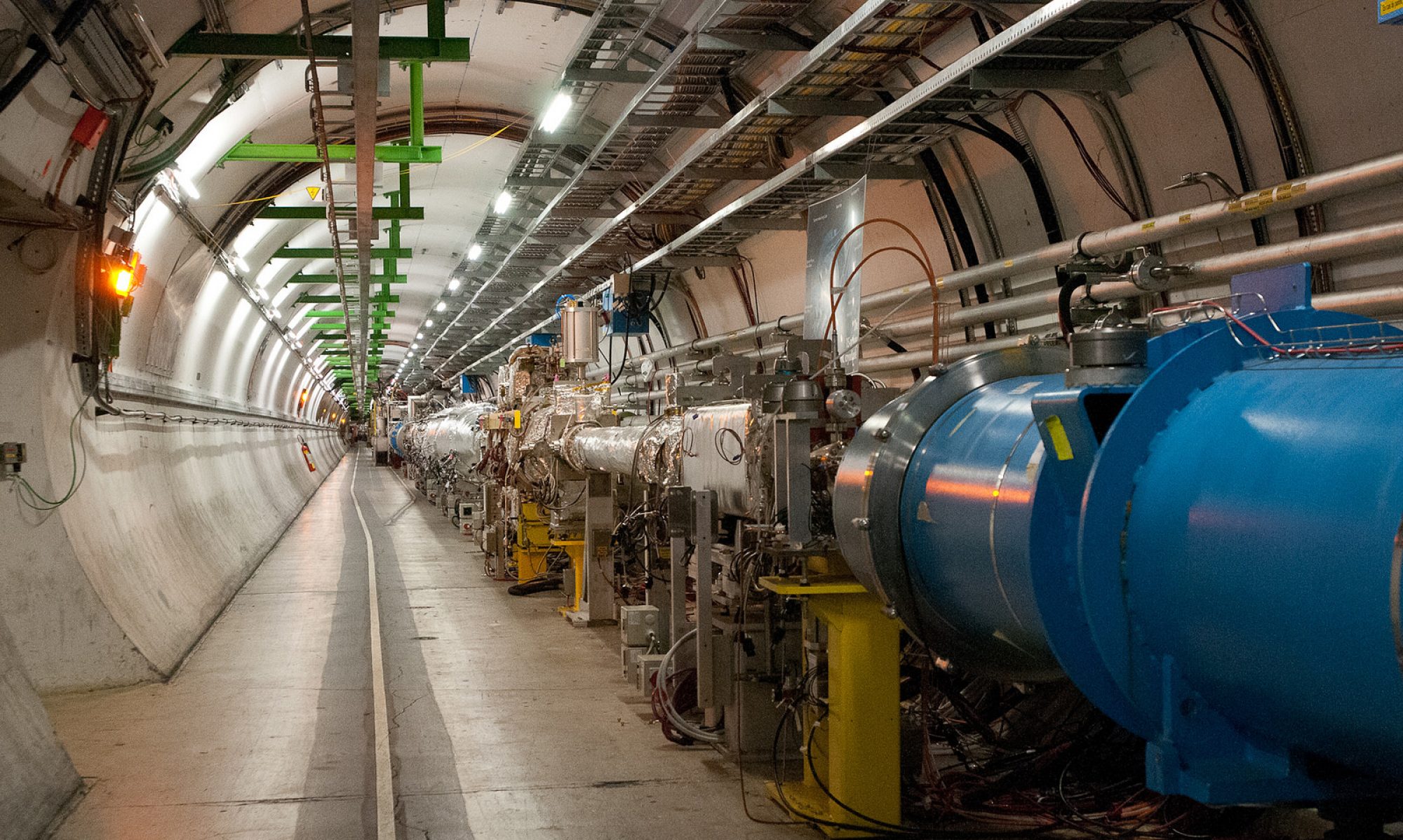

10:45 p.m., a cluster of massive buildings marking the location of the Point 1 Control Room for the ATLAS Experiment. ATLAS is itself 90 meters below the earth.

10:45 p.m., a cluster of massive buildings marking the location of the Point 1 Control Room for the ATLAS Experiment. ATLAS is itself 90 meters below the earth.It’s 10:40 p.m. when I leave building 1, cut through a parking lot, and head for CERN Entrance B. It’s only been 6 hours since I woke up; I’ve rotated my schedule to put myself on a night-cycle. This is not easy for a human being. We’re adapted to the sun, and we run our lives by it. The gentle rhythms of our biological clocks crave the day-night cycle. But here I am, a physicist in Switzerland standing at a crosswalk, waiting to step into the distant dark and down to the Point 1 Control Room.

The ATLAS Control Room, or ACR, is located in the back of a cluster of large surface buildings. I say “surface buildings” because these structures mark the top hat of ATLAS, covering the large shaft that descends down to the ATLAS cavern, 90 meters (295 feet) below the earth. Approaching the buildings in the dark is an eerie experience. You walk from the intersection of Route de Meyrin and CERN Entrance B, up a tree-shaded, unlit driveway to a long security gate. A wave of your CERN ID in front of the gate sensor starts the gate on a slow slide to the left, allowing you to squeeze through. The cluster of lighted buildings then sits in the distance, perhaps another 100 feet away.

We gather at the Run Control desk to discuss committing some configuration changes to a database. The LHC is currently down, addressing some issues with the CMS experiment.

We gather at the Run Control desk to discuss committing some configuration changes to a database. The LHC is currently down, addressing some issues with the CMS experiment. The ACR itself is abuzz with activity, even at 11pm. I relieve the previous shifter at the Trigger Desk. We exchange information about the day’s activities. The Run Control shifter, an old colleague of mine from Scotland, comes over and asks for my approval of the current set of trigger configurations and then about committing some changes to a database. Despite the fact that there are no beams in the LHC, it’s a busy night. I had been told by the previous trigger shifter not to expect colliding beams until at least 5 am.

There is a routine to a shift that I like very much. Most of it involves checking dozens of windows, each which displays some nuanced aspect of the ATLAS trigger system. The “trigger” is a computer hardware and software system whose sole job is to decide if a particular proton-proton collision is interesting enough to write to disk for further investigation. If the trigger isn’t running correctly, physics can be tossed aside and wasted. In addition to the technical routine, there is the job of interacting with colleagues in related systems, like the Data Acquisition Shifter who sits next to me, or the Shift Leader. It’s important to keep exchanging information while on shift, and work together to solve problems. There are always problems, and that’s the real fun of taking shifts.

The two coffee machines that serve the ACR. The Nespresso machine on the right is my favorite.

The two coffee machines that serve the ACR. The Nespresso machine on the right is my favorite.

To survive a night shift, even after rotating your schedule, you need coffee. Or, at least, I need coffee. Two floors up from the ACR is a pair of coffee machines that make decent espresso. I’m a big fan of these two machines; they’re really the unsung heroes of the ATLAS experiment. On the floor between the ACR and the coffee, painted on the wall along the staircase, is a mural of the ATLAS detector depicting different particles interacting in the equipment. The painting is 1:1 scale, meaning that as you walk up the stairs and follow an electron back along its illustrated path, you are getting a sense of the immense journey that this high-energy subatomic particle is making from the proton-proton collision that birthed it.

Whenever I am on night shift, I think about my mother-in-law. She’s been working in a bakery for decades, and that means she’s up between midnight and 3 am, in time to go in and do all the prep work and baking for the day. It’s a hard life, and she’s been doing it a long time. She does it because the job demands it – people want their baked goods first thing in the morning, when they get up to do their “normal” jobs at “normal” hours. For physicists on a major experiment like ATLAS, the data demands to be taken at all hours of the day. In fact, night is the most stable time to take data – the people that like to tweak the collider are home for the day, leaving a shift crew behind who are ready and eager to have stable operating conditions through the late hours of the night. On the experimental side, we welcome such conditions – stable beams mean steady data. ATLAS, and the other LHC experiments, will run 24 hours a day for most months of the year. a crew of hundreds of people per experiment is needed to maintain the detector. It’s not just the people in the ACR – the “seen” – it’s those who work in the satellite control room, in distant homes and offices doing remote shifts, and on-call experts who commit themselves to this task 24-hours a day for months at a time. Those are the “unseen”, the people without whom the experiment fails but who don’t get to be on the ACR webcam.

A 1:1 scale mural of a segment of the ATLAS detector, depicting in life-size the journey of different subatomic particles.

A 1:1 scale mural of a segment of the ATLAS detector, depicting in life-size the journey of different subatomic particles.

It’s 12:30 am. My shift is just beginning, and it’s starting to quiet in the ACR. The LHC is promising beams in the machine in 30 minutes or so. They aren’t messing with the collider settings too much, which means we may get steady data tonight. It occurs to me that I am almost on Dallas time, here in this distant control room for a global experiment. It’s dark outside, but I feel alive. There is a deep and substantial pleasure in committing yourself to an experiment like this, one which cannot be explained but through weak analogy to pride of place and service. We are subatomic shepherds, here in the ACR, looking to bring the data home.