I was recently a participant in a welcome event for pre-med students at SMU. The event started with a panel discussion, including members of the science faculty at SMU. It ended with a social event outside the auditorium. Jodi and I participated in the social event (the panel discussion was packed and well underway by the time we showed up) and met a bunch of pre-med undergraduates. Several of them were interested in what they would get out of taking physics (one made the common remark about having a bad experience in high school physics). Jodi and I took a holistic approach – discuss the exciting reasons for doing physics, but emphasize the applications of physics across boundaries.

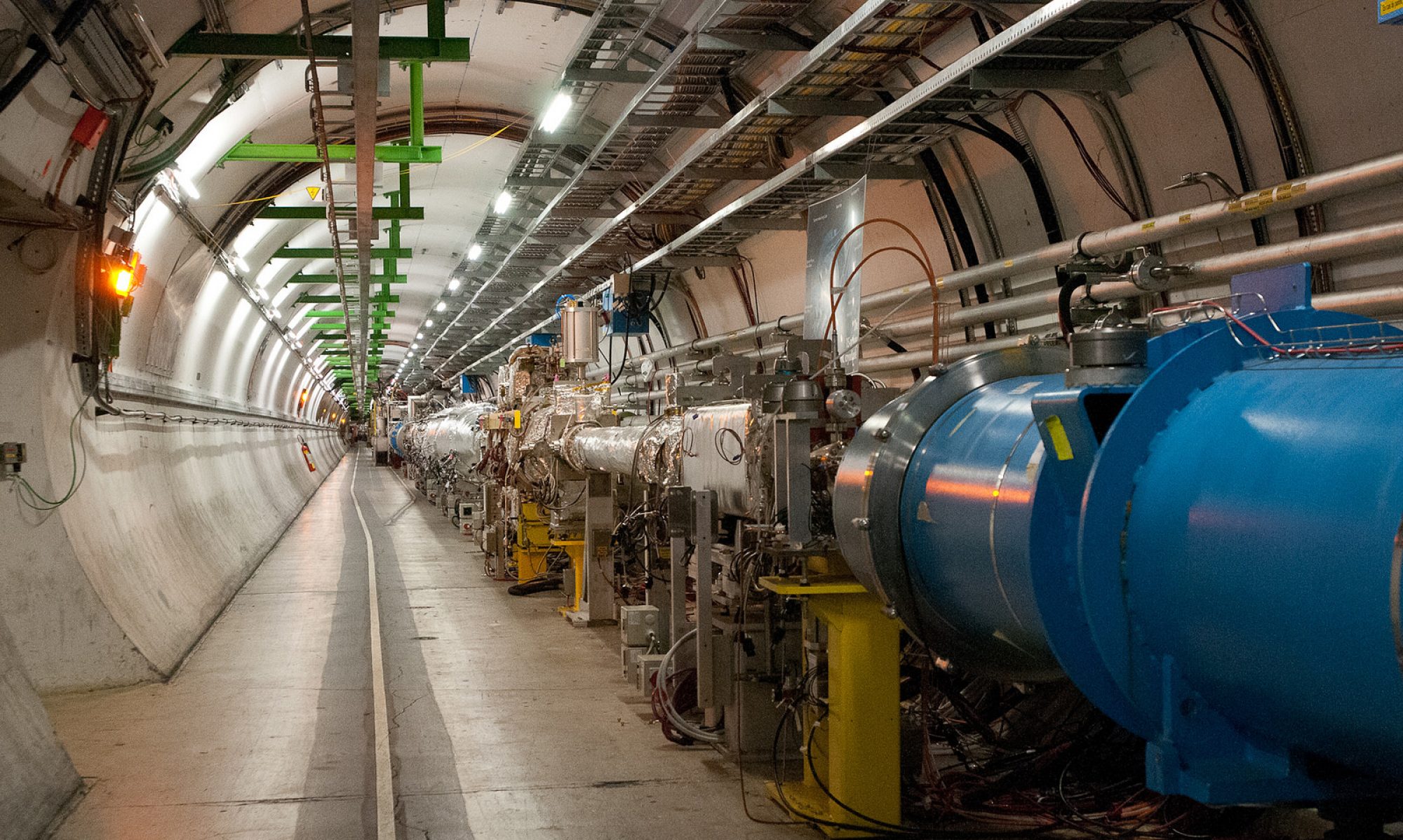

For instance, I enjoyed mentioning the role that subatomic particle accelerators play in modern cancer treatment. The statistic we used to bring to Washington D.C. was that 11,000 cancer patients every day are treated with medical accelerators. I mentioned the fact that subatomic charged particles are attractive because some of them can penetrate the body, doing little damage as they enter, and then dump all of their energy into the tumor. It’s like a guided missile for cancer.

There was definitely surprise from some of the students that physics plays this role. It was a pleasure to take this opportunity to start broadening them a little. Maybe they’ll take physics and hate it, or maybe they won’t take it at all. But the truth is that physics, like many other sciences, plays a central role in our lives. From medical imaging using antimatter (PET scans) to cancer therapies, physics is in all sorts of places. Let’s not forget the central role that classical mechanics plays in sports medicine (Newton, after all, can teach us a lot about bone breaking, shock and impulse on joints, and many other mechanical stresses on the body).

I learned today about www.acceleratorsamerica.org, a website devoted to promoting a symposium about accelerators and their role in the future of the U.S. From manufacturing to medicine, particle accelerators are playing an increasing and important role in our world. How does the U.S. remain viable in the development of this technology? These and other questions linger over this enterprise.

I like to look back at a haunting but uplifting photograph that a good friend of mine showed me many years ago. In it, a small boy is seen sitting, almost casually, under the watchful eye of a particle accelerator [1]. The black and white photo is of the first person ever treated by a particle accelerator in the Western Hemisphere. The article referenced here tells us,

[Henry] Kaplan and [Edward] Ginzton, PhD, professor of electrical engineering and of physics, developed the first medical linear accelerator in the Western Hemisphere, installed at Stanford-Lane Hospital in San Francisco. In January 1956 the machine was ready to be used on their first patient, a boy with retinoblastoma in his one remaining eye after surgeons had removed the tumor in the other eye. Destroying the tumor while sparing the eye would have been impossible with earlier, less-focused radiation sources.

“I will never forget the puzzled look on the face of the garage owner down on Fillmore Street when I asked him to borrow a heavy-duty automobile jack,” recalled Kaplan in the book. “I explained that it was to carry a large block of lead with a pinhole in it, to enable us to position that pinhole day after day for six weeks directly opposite the tumor in the boy’s eye while missing the lens and cornea.”

As in all things in learning, don’t forget that learning in a narrow lane won’t give you the creativity you need to do great things. Expanding yourself a little, challenging your educational comfort zone, leads to greatness. If physics kept to physics, biology to biology, chemistry to chemistry, how many important medical procedures and treatments would have been missed? How many lives lost?

A little physics can go a long way. Heck, it might save a life.

[1] http://news-service.stanford.edu/news/2007/april18/med-accelerator-041807.html