We met for breakfast at Izzy’s Brooklyn Bagels at 10am, and fueled up for our first day here in the Bay Area. After a short walk back to the hotel, we piled in the giant van we’ve rented for this trip and, in the cold drizzling rain, took a short driving tour of Stanford University before heading to SLAC. We arrived at SLAC just in time to grab a bunch of tables in the cafeteria and hold them until some friends and colleagues arrived to eat lunch with us. Post-docs from SLAC and the University of Maryland, as well as our Stanford grad student tour guide, Nicole, mixed it up with the students and answered their questions about physics, experiments, and life in science. Just behind us, at one of the tables, sat one of SLAC’s own three Nobel Prize winners, eating lunch with his own friends and colleagues.

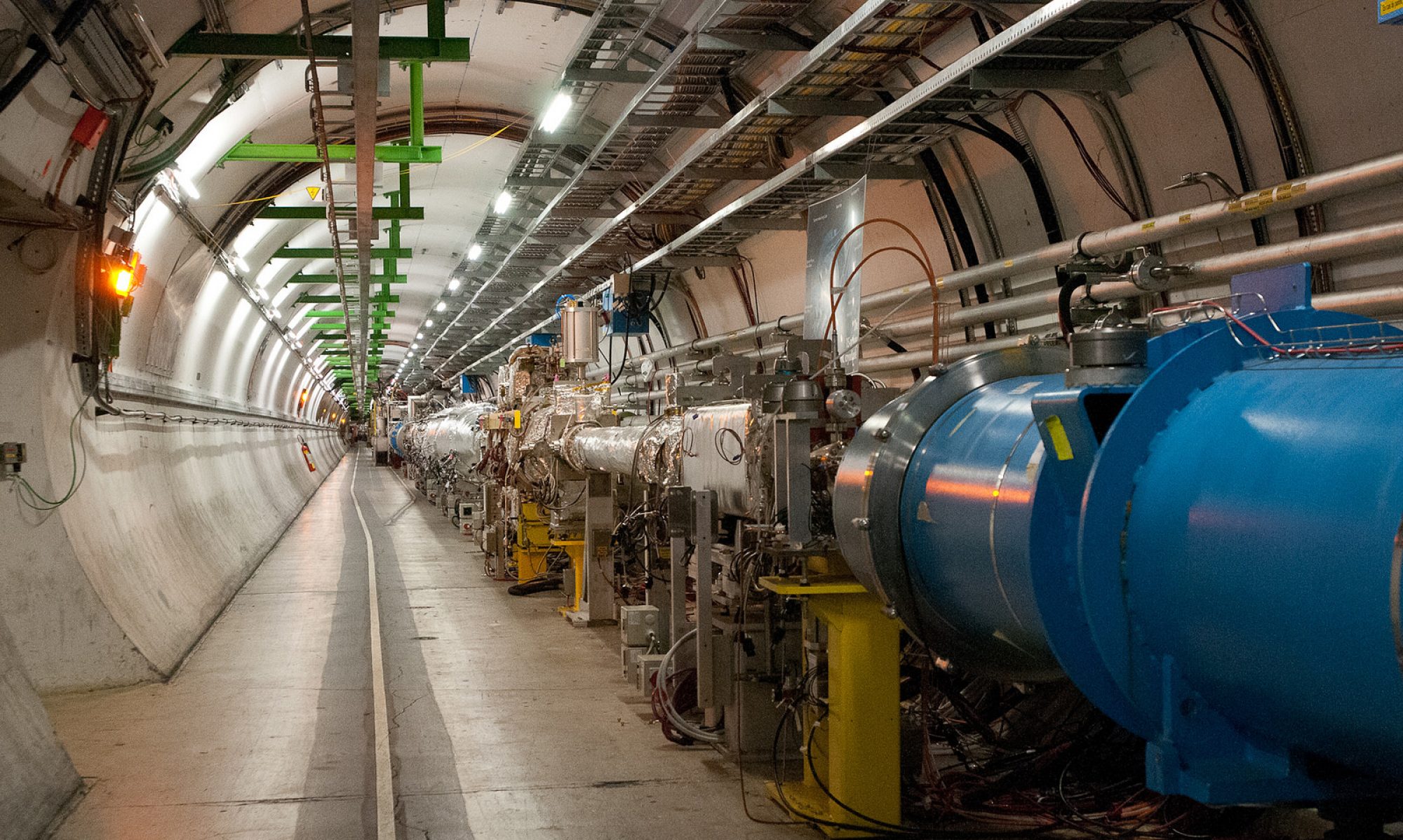

Our tour began at 1pm with a short overview of the laboratory. Nicole delivered this presentation from the SLAC Director’s conference room. We then piled into the van again and headed into the accelerator area. Our tour started at the Klystron Gallery, one-quarter of the way along the two-mile linear accelerator that is the heart of SLAC science. The buzzing microwave generators, the klystrons, were busy feeding energy into the accelerator (25 feet below us) for use in the Linac Coherent Light Source. We stood in the gallery hallway, stared off into infinity (OK, well, to the vanishing point of the human eye), and then piled back in the van.

(for more photos, visit http://snappy.cooleysekula.net/thumbnails.php?album=10)

We saw the Main Control Center, the heart of accelerator operations at SLAC, and then took a short walk down a dark, cramped tunnel to the Research Yard. It was here that, in the 1960s and 1970s, the experiments were done that demonstrated that protons have substructure. This substructure came to be interpreted using the “quark hypothesis,” long unfavored as an explanation of proton and hadron structure until mountains of evidence appeared in support of it. We paused on the steel walkway, two stories above the ground, and looked out over the yard at the massive concrete end stations A and B, as well as the new extension of the linear accelerator that serves the light-source community at the laboratory.

We next stopped at the Stanford Large Detector (SLD), which ceased operations in the late 1990s around the time BaBar was completed and began operations. Donning hardhats, we were shown parts of the detector before descending into the detector pit for a quick photograph. We wrapped up the tour in the BaBar detector hall, where the experiment stood largely disassembled; only 2/3 of the barrel and back endcap remain, and the tracking system has been gutted from the detector. It’s the first time I’ve watched an experiment important in my own career be taken apart and shipped away. It was a deeply meaningful, and slightly painful, moment. I was happy, however, to pose in front of BaBar with my two undergraduate researchers, Landon and Matthew, who have done their projects on data from the BaBar Experiment.

We wrapped the day with coffee and rest in the Kavli Astroparticle Institute, before heading off for a nice casual dinner at In & Out Burger, a staple of California fast food. It was a nice counterpoint to the spicy and exotic Thai food we feasted on last night.

Tomorrow, we head to the top of Mount Hamilton to see the Lick Observatory. Among its many studies, it was the site of the first U.S. test of General Relativity, and should afford spectacular views of the entire Bay Area.