This semester, I am conducting what is, for me, an experiment in teaching. The seeds of this experiment were planted last semester, and prior to that by a long line of physics education research. This experiment will place an even greater burden for learning on the student, but I believe that it will allow me to emphasize the development of skills in the classroom while using time outside the classroom to get students to engage in the fundamentals of the material. I’m “flipping the classroom.”

“Flipped classrooms” are far from a new idea. In fact, one of my colleagues at SMU, Pavel Nadolsky, has been advocating for this approach to teaching since before I arrived at SMU. The idea is fairly simple: students read or engage in other preparatory material before coming to class. Class time is reserved for discussion and problem solving, with an emphasis on application of ideas learned outside of class. This is in opposition to the “chalk talk” or “sage on the stage” approach to classroom time, where an instructor talks and students listen, take notes, and are supposed to passively absorb new material.

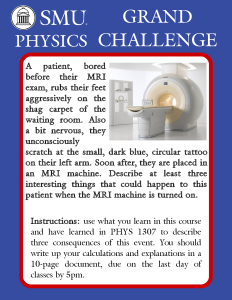

Of course, I am still assigning homework – I need that to assess the development of skills and the absorption depth of new ideas. Students still have exams – 4 during the semester – to assess independent learning (albeit under an unnatural time constraint). Rather than a comprehensive final exam, however, I am assessing high-level, overall absorption of material via the assignment of a “Grand Challenge Physics Problem.” This is a non-textbook problem where students are expected to work together in randomly assigned teams to take class material and use that to calculate answers to the question. The question is open-ended, encouraging creativity, but the answers must be defensible. This is worth 25% of their final grade, and of that 25%, 20% comes from the grade on the group report (10 or more pages in length) and 5% comes from final exam questions that assess individual team members and their understanding of their team’s answers.

It’s been a fun experiment. I already had developed video lectures on core material for last semester. I’ve now expanded that material (I’m still not happy with all of it… but I can revise as I go forward). I’ve added an “instructor problem” to class time, where I demonstrate how to approach a problem involving new material, and a “student problem,” which the students try to solve in small groups of 2-3. There is peer learning, peer mentoring, engagement with the instructor, and an assessment of common issues or challenges that arise.

Let’s see how the semester goes. It’s still young. But so far, I’ve found this a much more interesting class to teach than constantly having to know that I have to perform for 80 minutes while students listen in silence. That’s not good for them. It’s much better to have a lively and challenging problem, with new material to be applied quickly, and then the chance to ask each other questions and get me to try to nudge them in various directions.