[Author’s Note: thanks to Ray and Luke for their excellent comments. I’d like to note that, while I leave this post up for now, I don’t agree any longer that gun licenses are a good proxy for gun ownership. There are other studies now available regarding things like “stand your ground” laws and their effect on violent deaths (they cause increases in them, and not just for the criminal), but the point is that data on this issue is hard to come by. As a result, it makes drawing conclusions difficult. Please note that there is a difference between a “lack of good data” and a “lack of violence linked to kinds of weapons” – don’t mistake one for the other.]

Absent from a lot of the rhetoric on gun control or the second amendment has been something that, as a scientist, I feel is critical to the whole discussion: data. Data paints a picture that lets us understand the context of our arguments and the consequences of our choices. While news reports have given numbers about gun mortality or gun ownership in isolation – maybe for just a single year – I thought it would be instructive to look at gun ownership and gun violence together over a long period of time. Here were my criteria:

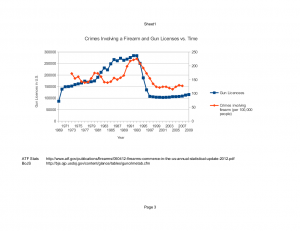

- I used data from the ATF (http://www.atf.gov/publications/firearms/050412-firearms-commerce-in-the-us-annual-statistical-update-2012.pdf) to obtain the number of gun licensees in the U.S. from 1969 to 2011, the first and last years for which these data were available. These licensees include: dealers, pawn-brokers, collectors, importers, and manufacturers. According to the ATF, most licenses in existence are through firearms dealers. Gun licenses are a proxy for gun ownership.

- I used data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/glance/tables/guncrimetab.cfm) on the number of crimes involving a firearm. Why not mortality? The problem with mortality is doctors – they’ve gotten so darn good at saving lives thanks to science and technology that this can hide the real trend in gun-related violence. Instead, I sought the rate (per 100,000 people) of crimes involving firearms (that includes handguns, shotguns, and rifles). This tells a broader story, about both intent to kill and actual killing. Intent to kill is not corrected by a surgeon’s blade, so these numbers should not be muddied by any improvement in emergency healthcare in the U.S.

Here are the data:

The data tell an amazing story. Firearm-related crimes typically trend in response to changes in gun ownership. When gun ownership (licensees) rises quickly from 1981-1993, crimes involving firearms rise with a lag. When the Brady Act, which tightened rules on obtaining a handgun license, and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which restricted assault weapons sales, go into effect in 1994, the number of firearms licensees plummets. Shortly after this, crimes due to firearms also begins to plummet sharply. Over the period of 1993-1999, the number of licensees dropped by more than half (from about 270,000 in 1993 to about 100,000 in 1999) and in that same time period the firearms-related crime rate dropped from about 225/100,000 to about 125/100,000, or a reduction of about 45%.

Now, you can go ahead an continue fighting about Constitutional rights. But don’t forget that many of the Founders of this nation were scientists – Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, and Paine – and they would respect decisions based on data that are also consistent with the laws of the land. Consider that before you wrap yourself in data-less rhetoric.

3 thoughts on “Data on crimes involving guns”

Hi Steve! Very interesting statistics. I do have a question: aren’t federal firearms licenses needed to sell a firearm, not to buy a firearm? If so, then the assumption that “gun licenses are a proxy for gun ownership” might be a bit misleading. It might be interesting to try to estimate how many firearms are in the U.S. and how much that number changed across the big dip in crimes and licensees in 1994. It may be that the number of federal firearm licensees (i.e., sellers) is more closely related to the first derivative of the number of gun owners than it is related to the total number of owners. Just a thought. Or maybe I’m completely wrong in thinking that the licensees track sellers more than buyers. Thanks for the interesting and illuminating info!

Ray has a good point. I am surprised I didn’t realize this before, but the total number of guns or gun owners in the U.S. is on the same order as the population. The data you present do not indicate how many guns are sold per licensee or how many guns sold before the decline in the 90’s are still functioning. So, I think your claim that “Gun licenses are a proxy for gun ownership” is questionable.

Indeed, a study from the National Academies ( http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10881 ) cites the lack of good data on gun ownership as a key obstacle to the kind of data-driven discussion we seek. Chapter 3 shows their estimates for gun ownership in the US.

Hi Luke and Ray,

Thanks for the comments on this post. I definitely need to weaken the conclusion. I’ve been spending a few days trying to find an accurate proxy – as the NAS notes, it is VERY HARD to find reliable data to use. The fact that gun registration is a non-starter makes doing this very hard. I had hoped that gun licensees would be a close track to gun sales, and that that would be a close track to gun ownership. The more I dig into this, the more and more I agree with your comments.

I noted recently that a study has been published looking at violent deaths and their rate before and after “stand your ground” laws were passed. NPR had a good, short story on this paper (http://www.npr.org/2013/01/02/167984117/-stand-your-ground-linked-to-increase-in-homicide). In short, where such laws are passed the rate of violent deaths increases compared to before the law was passed and compared to surrounding counties, etc. that do not have such laws. That’s a better example of increased license to kill leading to more violent killing, but it’s not necessarily telling of the correlation between kind of weapon and probability of violence. It only tells you that when violence is permitted with fewer severe consequences (for one of the parties involved), violence happens more often.

This is a complex issue. I missed the mark with my data, even if the trends themselves are still interesting.