People talk about getting cancer like they talk about winning the state lottery. Winning the state lottery is, by design, an extremely improbable event. Unlike the state lottery, most of us stand a fair chance of getting cancer at least one time in our lives. And unlike for winners of the state lottery, where past success is totally independent of future chances of winning again, for those who win the cancer lottery the chances of winning a second time go up significantly. I’m not talking about brain cancer, or prostate cancer, or some other specific horrible cancer that makes headlines. I’m talking about any cancer – any alteration of our own genetic code that leads to the successful development of aggressive tissues that cannot be corrected or eliminated by the body’s mechanisms for weeding out mistakes.

People talk about getting cancer like they talk about winning the state lottery. Winning the state lottery is, by design, an extremely improbable event. Unlike the state lottery, most of us stand a fair chance of getting cancer at least one time in our lives. And unlike for winners of the state lottery, where past success is totally independent of future chances of winning again, for those who win the cancer lottery the chances of winning a second time go up significantly. I’m not talking about brain cancer, or prostate cancer, or some other specific horrible cancer that makes headlines. I’m talking about any cancer – any alteration of our own genetic code that leads to the successful development of aggressive tissues that cannot be corrected or eliminated by the body’s mechanisms for weeding out mistakes.

It’s, in some ways, remarkable that most of us don’t get cancer more often. Every time our cells divide, unzipping our DNA to prepare for replication, there is a chance that one or more base pairs will be erroneously copied, leading to a flaw in the replication process. It’s also possible for strong chemical reactions to lead to disruptions in copying, initiated by the ionizing of molecules due to effects like exposure to ultra-violet light or the random interaction of a high-energy cosmic ray inside our tissues (something that happens quite a lot). The good news is that most errors in copying lead to genes that cannot function properly, or that result in the production of molecules that fail to support cellular mechanisms. For a variety of reasons, cells tend to die off after such mutations and are simply removed by the body as waste. Most people are blissfully unaware of the sheer numbers of mistakes their own bodies are constantly dealing with in an attempt to perpetuate the life of the host, thus increasing the chances of passing along host’s genes and propagating the species.

The fact that cancer is not the leading cause of death, or a process that affects 100% of all humans all the time, is a testament to the long march of biology over millions of years. Driven by the simple process of environmental pressures, be they physical, chemical, or biological, the process of cellular reproduction has evolved with checks and balances in place to minimize errors in duplication. While errors can be troublesome or useless, they can also be useful – in fact, mutation is the essential agent of biological change while natural selection picks the winners and the losers. But that same process can sometimes result in tissues whose growth is unlike the parent cells. In their own effort to procreate and perpetuate, they invade neighboring tissues or hitch a ride in the bloodstream and land in some other poor organ. Cancer is, quite simply, what happens when mutation results in a new organism that is unable to live symbiotically with the host, or to be destroyed by the host. It’s a sideways march of natural selection, one of those accidents whose chances can be increased by sun exposure or exposure in large doses to certain classes of chemicals. It doesn’t tend to end well for the host.

The consequences for the host can vary, from physical deformation to death. The treatments for cancer can vary; the body can already do a lot to evict troublemakers, but when it fails a person can be faced with a range of choices, from chemical treatments to surgery.

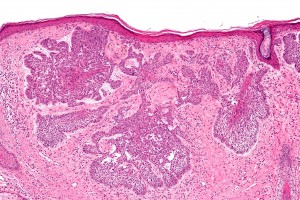

I say all of this because it’s recently been made clear to me that I have won the cancer lottery. My prize is thankfully small – a growth of basal cell carcinoma on my face, just below my left eye. Basal cell carcinoma is probably the most easily treated cancer, with a scary name, a very high success rate, and only in the very rarest of cases leads to complications that can be life-threatening. The growth of the carcinoma is usually very slow, but left unchecked it will eventually do serious damage to surrounding healthy tissues. Treatments vary, but the most successful currently documented treatment is the Mohs Surgical Method. This is what I will receive. I like the Mohs Method because it appeals to me as a scientist.

In the Mohs Method, a minimal section of skin will be removed from my face, going deep enough and wide enough to try to encompass the carcinoma. I’ll be awake for the whole process, with a local anesthetic applied to my face. After the first removal, I’ll be able to sit in a waiting area while the skin section is frozen, stained, and sliced. The tissue will be assessed under a microscope, looking at all the edges to see where basal cells extend beyond the periphery of the surgeon’s cuts. Those locations on my face will then be revisited with the scalpel, removing more tissue for further scrutiny. The cutting stops when the basal cell growth no longer crosses the surgeon’s cut boundaries. This process is expected to take no longer than four hours, which seems like a pretty minor investment for a 98-99% success rate.

The wound will be sutured in such a way as to follow the wrinkles (smile lines) on my face, so that any long-term scarring will blend with natural lines forming with age on my face. I’ll be sent home to rest for about seven days, and I’ve been told to expect significant swelling on the left side of my face. The surgeon said that after a few days it will look like somebody socked me in my left eye, so this will be a new experience for me. I’ve been prescribed total rest for that period, and no lifting of anything over 10 pounds to avoid popping the stitches. After about seven days, assuming the wound is healing well, the sutures will be removed and I’m essentially free to go about my life after that. The scarring will largely vanish over the course of about three weeks.

To be fair, I had this coming. After all, as a physicist I spend my life modeling nature, designing cuts to select interesting phenomena, and then applying those cuts to better isolate and understand the world. Nature just seems to want to return the favor . . . and I can respect that.