Physics is a good story. The muon collider is one amazing chapter in that story, one which has yet to be written but which has been colorfully outlined. Jodi’s experiences at the WIN07 conference in India reminded me tonight of this incredible instrument, and I want to here share my thoughts on this story.

The tale of the muon collider begins after the first triumphs of the Standard Model. In the late 1970s, papers appeared which outlined the idea of a muon storage ring, a particle accelerator system capable of producing and storing muons for use in particle collisions. Muons are the heavy sibling of the electron, and the middle-child in the line of electrically charged “leptons” (the electron, muon, and the very heavy tau). Because the muon is so much heavier than the electron, and thanks to quantum mechanics, it doesn’t stick around very long – just 2 millionths of a second, in fact. Electrons, by comparison, live forever (there is nothing lighter than them into which they can decay, and still conserve things like electric charge and energy).

Muon storage is technically improbable. I say improbable because if I say “impossible”, I’ll be wrong. We know muons live only two millionths of a second, and we know they are hard to produce in large numbers. We know that even once created, they would be hard to accelerate long enough before most of them decay away, leaving few of them to actually use in the collider.

But none of these things is impossible, so I say that building and operating such a thing is *improbable*. Largely, this is because there hasn’t been a lot of money available for a concentrated, “human genome” style scientific effort focused entirely on overcoming the technical challenges of creating, storing, and colliding these short-lived particles.

It might sound, at this point, like the decay of the muon is a problem. Not so – the decay of the muon is a problem only in the context of *colliding* muons and anti-muons. In the case where you’re interested in an intense beam of *neutrinos*, the decay of the muon is a huge benefit. Being able to mass produce muons, accelerate them in a storage ring, and letting them decay into neutrinos, would enable us to produce a high-intensity, tightly focused, high-energy beam of muon neutrinos. Such a feat has never been accomplished by these means. While such beams exist, as at Fermilab and the MINOS project, they are produced from the decay of strong mesons. Relying on these mesons for the production of a beam of neutrinos is a bit like relying on the “Peanuts” character, Pigpen, to clean your house. Sure, your house will probably be cleaner than when it started. But it will still be dusty and grimy, because the guy cleaning it is . . . well . . . a pigpen.

A muon-produced beam of neutrinos is like having your dirty room immersed in a Class 1 clean-room environment and then scrubbed by sterile Roombas – we’re talking super-clean. At least, in comparison to producing them from strong mesons. The dream of such a beam has been expressed by a great many people, and the statement is always that a “muon storage ring is 20 years off.”

I remember that at a conference in Madison, Wisconsin in 2002 or 2003, an Indian physicist stood up during a parallel session and gave a very intriguing talk about siting a neutrino experiment in India which would catch the neutrinos from a muon storage ring. The idea was simple: collaborate internationally to site and construct a muon storage ring, perhaps with the idea of “upgrading” it someday to a collider. Meanwhile, operate the ring like a neutrino factory, designing the packets of muons to circulate at just the speed needed so that most of them decay into neutrinos at a particular point in the ring. This would result in a beam of neutrinos shooting out with the same profile as the muon bunch, and if well-chosen it could be aimed through the Earth and into a remote site in India. This proposal, the INO Experiment, is still being talked about today.

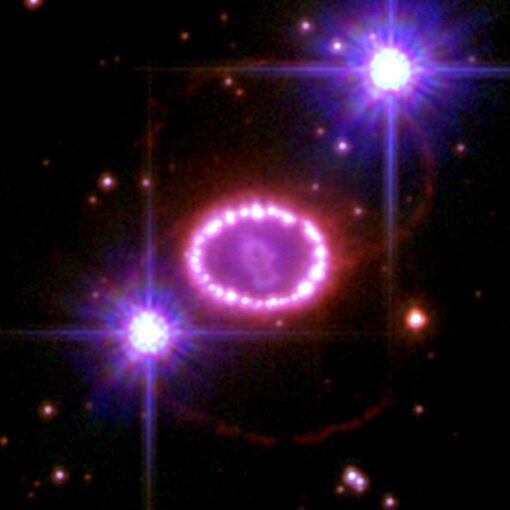

A muon storage ring is the beginning of something greater, and it’s a technology that has always excited me. As a neutrino factory, one would possess an internationally accessible tool for creating a clean, extremely well-characterized beam of neutrinos. Such a beam would crack open the still-sealed doors that might lead us to a real understanding of the “whys” and “hows” of the mysterious neutrino. Configured as a muon/anti-muon collider, such a machine would be an *unprecedented* tool for probing nature on extreme scales. The muon, being a rare particle with deep connections to very high energy scales (like those that existed closer to the beginning of the universe), would allow us to probe the universe in a means never before achieved.

Jodi told me tonight that INO is alive and well in the minds of Indian physicists. I applaude the Indian physics community for sticking with this idea. It’s a great idea. Perhaps India, unlike the U.S., will be able to turns its sensible investment in the physical sciences, in part, toward a “human genome”-style effort to overcome the technical challenges of the improbable, but far-from-impossible, muon collider.