There is a coming change in the American landscape of particle physics. It’s an interesting violation of some basic tenets of physics. As the center of gravity shifts from the U.S. to Europe, more and more of the weight of the field is being born by fewer people here at home. As I said a week ago, I have been and will continue to be lamenting the departure of many friends and colleagues as they trek East to Switzerland and the surrounding countries [1]. It makes my heart heavy, my mind troubled. What will this country look like as its focus begins to shift from labs centered on basic research to those with an awkward pitchblende of basic and applied science?

SLAC is a good example of this. We have just wished our previous Director well as he steps down. He was a particle physicist, the third Director of the lab and the third hailing from that field. It was an emotionally painful ceremony for me, because under his Directorship I came to SLAC and started my graduate research, with his advice and input we informed our lobbying trips to Washington D.C., and with his encouragement I gave my first public lecture. I was by no means close to him, but it’s a bit like seeing a teacher who was important in your life move into another position, leaving a vacuum that cannot be filled in quite the same way.

SLAC will no doubt lead a search for a director that best fits the future program of the laboratory. Particle physics will begin playing a smaller role, more on par with the non-accelerator-based projects of the past. Astrophysics is becoming a growing and successful centerpiece of the lab, a move which I applaud and perhaps could even make my own home someday. The real heart of the lab is still the linear accelerator, but now turned into the world’s most powerful x-ray free electron laser. It’s a thing of beauty, and beam capable of imaging chemical reactions as they occur and turning on its head our understanding of the basic structure of proteins and new materials.

While I am in awe of the engineering feat of this laser, and while I am excited by the program of astrophysics, I know that a turning point has been passed when particle physics was a leading mission of the lab. The accelerator will no longer feed the hungry matter/anti-matter storage rings, no longer enable the creation of “little bangs” that tell us about those first moments of the universe. Instead, SLAC will help build satellites, to build cameras for telescopes, to run simulations of mind-bogglingly large galactic clusters. It will have a vibrant program on the LHC, and a vibrant program to design future accelerators and detectors. It will make stunning leaps in ultrafast, ultrasmall applied science. But I’ve come to understand that SLAC will, for some time, look more outward and less inward.

One could look at this in many ways. The cosmology revolution of the past decade has made it finally possible to make serious measurements of the universe by looking outward. Gone are the hard-fought but large uncertainties of the last generation of telescope and satellite observations. Now are the days of precision cosmology, of concordance models of the universe that give firm predictions about what lies out there. Now is the best time to inject an investment of mental capital into this field, because it does seem the most promising for making progress on human knowledge about the universe.

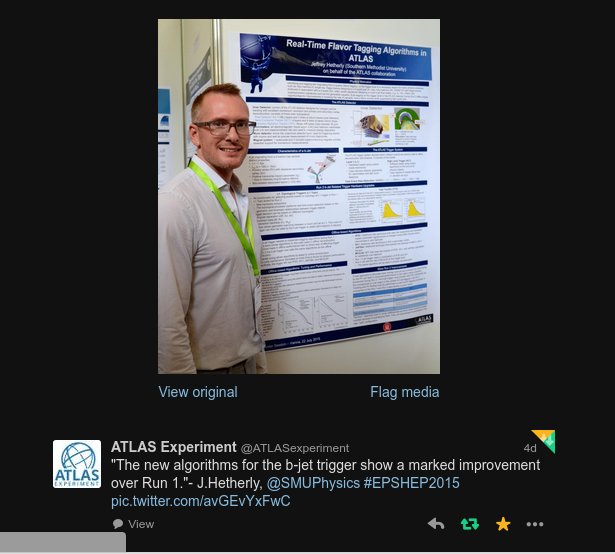

The flip-side of that coin is that looking inward has become a desert-crossing van running on fumes, with no gas stations in sight. That’s not entirely true – a service station with a flashing neon sign reading “LHC” looms on the horizon, but like a mirage seems to get a little further as we approach it. No doubt that the LHC will turn on next year, and no doubt that the massive talent centered in Geneva will make that marvel of the world work. I have no doubt that the countless hands and minds that built ATLAS and CMS will have their skyscraper-sized particle detectors quickly looking inward at the fires of creation. As in any scientific search, there is still a question: will they see anything? Will the mirage move further away, despite this next best push to squeeze the fumes into usable gas?

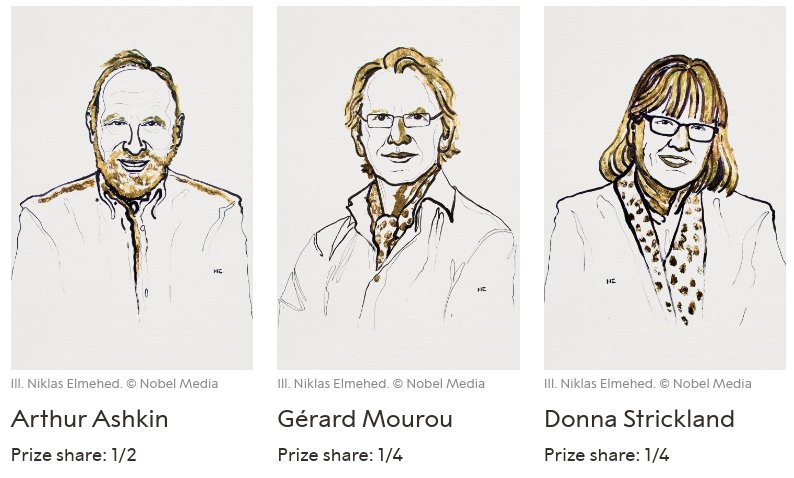

These are challenges to me, my friends and colleagues, and an entire global field of study. They are challenges no less than those faced by the giants on whose shoulders we stand, perhaps made a little worse by the funding climate here in the U.S. and elsewhere. Each, in our own way, will rise to this challenge. Many have chosen the LHC, others are looking to flavor physics, many have turned to interrogate the neutrino, and as many have turned to dark matter to grasp it by its ethereal shoulders and shake it till it talks.

I hope, above all other things, that we will live up to the rhetoric we’ve spun for this field. I hope that we will continue to look outward and inward, as we have promised to do. There are many of us who want to do either, or both. The public that funds science and becomes its practitioners, must adopt a bold approach to making progress: like the universe, we must be a whole with varied parts that all work to understand a great history, composed of an untold number of individually shining stars.