“You work on that big collider in Switzerland?” the border control agent asked me.

“That’s right,” I replied.

“Had some trouble a few year’s back, didn’it?”

“Yeah, but we came online last year and we’ve been ramping up since then. In just 5 weeks we’ve taken almost as much data as we did between March and November of last year.”

“Well, all right then. Enjoy your stay. Cheers,” he said, flashing me a dashing smile and handing back my passport.

This was one of a couple of random encounters with well-informed British citizens. Another came from the last train from Stratford-upon-Avon to Oxford. A tall, pleasantly intoxicated man named Andy sat down across from Aidan and I. His brightly colored sweater matched the brightening hue of his face as he struck up a conversation with us. When we mentioned we were physicists, he asked whether or not we were involved in that big experiment in Sweden or wherever (he was a little drunk, give him some credit). We chatted with him about his work and our work until we reached is stop in Leamington Spa. A number of times during the conversation, he kept remarking how “f’ing awesome” it was that we were able to do the kind of research we were doing. Without any mocking, he tossed a pleasant salute from the platform as our train pulled away from the station.

From the in-your-face intellectual density of evolutionary evidence in the Natural History Museum, to Charles Darwin’s visage on the 10-Pound note, to these little slices of British citizenry who not only knew about the LHC but seemed to delight in learning more, it was quite a strange affair to be in a country that seems so culturally devoted to science. In contrast with America, where every day seems a struggle against the long night of a dark age, Britain was a golden shaft of brilliant sunlight in a dimming world.

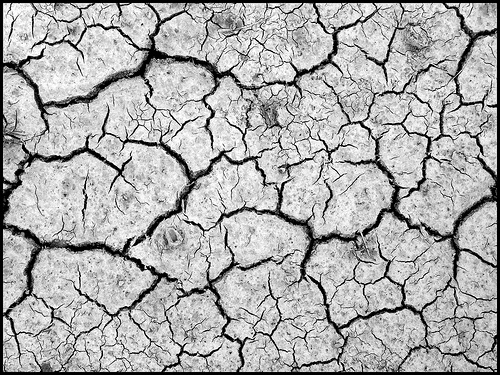

At the same time, I fear for my British friends. Their government is making more and more draconian cuts to their science budget. How long can a society steeped in science remain so when their government daily de-prioritizes the very firmament of their intellectual well-being? And what does this portend for America, and even the rest of Europe? America and Britain have long looked to each other for a sense of priority. I fear that all our allies may soon fall prey to a dark age of short-term thinking and depreciation of the cultural value of science.