The Republican Presidential Candidate debates (and all the media that encircles them) are a great place to look for examples of poorly applied thinking. Specifically, it’s a buffet of examples of pseudo-scientific argument. In this post, we’ll use one example that stemmed from the most recent CNN/Tea Party Express debate to highlight the danger of the anecdote.

First, what is an “anecdote?” The Merriam-Webster dictionary provides the following definition: “a usually short narrative of an interesting, amusing, or biographical incident.” [1] According to that same source, the word derives from the Greek word anekdota, which means “unpublished items.”

Anecdotes are a popular staple of the campaign trail. Candidates of all stripes use them to make themselves appear more relatable to their audience. They seem to be used to serve the role of a kind of parable – an anecdote usually is meant to contain a meaning or truth upon which the candidate builds an argument or with which a candidate counters their opponent.

Anecdotes are not a form of scientific evidence. Why not? First, they are usually second-hand information, at best. The person telling the story is almost never the participant in the story; rather, the story is about somebody else. You’re lucky if the anecdote resulted from a direct eye-witness event.

Second, an anecdote is a form of witness testimony that may be first-hand, but more likely has been transferred by an oral tradition from person to person (with the usual change in details or embellishment of events resulting from the transfer). Witness testimony is a form of legal evidence but is not a form of scientific evidence. Why? People lie. Even when they do not lie, people mis-remember events, or miss the full detail of an event, or both. Even when they do accurately recount an observation, they may assign causation in the sequence of events even though the relationship between the sequence may be accidental, coincidental, or completely random. The point is that people are fallible; the eye is fallible, the ear is fallible, and the mind is fallible. A single story cannot then be relied upon as the sole basis of a scientific argument. It may be the seed of an evidence-gathering cycle, but in and of itself the anecdote – a form of witness testimony – is not primary evidence. For an overview of the the fallibility of eyewitness testimony, see Ref. [2].

With all of this in mind, let’s look at the fallout from an exchange between Presidential Candidates Rep. Michele Bachmann and Gov. Rick Perry [3]. The exchange focused on Rick Perry’s executive order requiring young women (albeit allowing for parental opt-out of the requirement) to be vaccinated against the Human Papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is strongly linked to cervical cancer, is carried by men and women, and is sexually transmitted. That executive order was overturned by a veto-proof majority of the Texas Legislature. NPR ran an excellent story on this strange episode: a staunchly Republican Governor, professing support for individual liberty, issued an order requiring young women to receive a vaccine (albeit with a parental opt-out) [4].

This post is NOT about the political, policy or rights issues raised by his decision (however, see the “footnote” near the end of this post). Rather, this post is about something Michele Bachmann said on the “Today Show” on the morning after the debate [5]. She was discussing her position on the vaccination of young women against HPV. She relayed an anecdote told to her by a debate audience member after the event.

” . . . all innocent little 12-year-old girls or 11-year-old girls in the state of Texas would be forced by the government to take an injection of what could potentially be a very dangerous drug . . . I had a mother last night come up to me last night here in Tampa, Florida after the debate. She told me that her little daughter took that . . . vaccine and suffered from mental retardation thereafter. It can have very dangerous side-effects . . . people have to draw their own conclusions.” (Ref. [5])

Let’s parse that argument. Bachmann states her thesis – that the vaccine could be potentially dangerous. She then cites her evidence: a single anecdote from a single mother that connects two events, the receiving of the vaccine and the onset of some kind of mental retardation. Bachmann then repeats her thesis, and leaves the final decision to an audience that, one assumes from her argument, she believes she has now informed with this argument. This unit of speech represents the fullness of her argument.

What is missing here? She cites no medical literature to back up her statement. Let’s look at the literature on this issue.

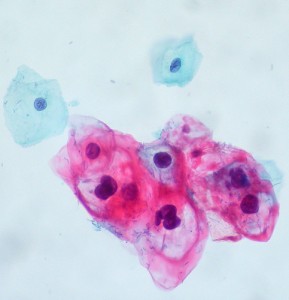

There are some relevant numbers in making an informed assessment of the risks associated with vaccination. First, what is the risk from the disease prevented by the vaccine? The numbers I cite here are all taken from Ref. [6], an article entitled “Epidemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with Cervical Cancer” from the New England Journal of Medicine. This article has been cited over 2600 times. The authors pooled data from 11 case-control studies of cervical cancer, including women with and without symptoms of the cancer. Almost 91% of the women in the group with cervical cancer also had HPV in their bodies (evidenced by the detection of HPV DNA in cervical cell samples), whereas only about 13% of the control group had positive results for HPC DNA in their cervical cells). Cervical cancer was once the leading cause of female cancer deaths in the U.S.; in the last 40 years, the rate of death from this cancer dropped significantly due to screening (e.g. Pap tests). In 2007, the most recent year for which data are available [7], over 12,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer. Since the cancer is linked strongly to a virus, and the vaccine prevents against the virus, about 90% of these cases were preventable.

Based on 2007 census numbers, this number of cases corresponds to 0.008% of the female U.S. population (and thus 0.004% of the U.S. population). Each year, about 0.001% of the U.S. population dies from cervical cancer.

Let’s pause for a moment and compare this vaccine and its associated preventable disease with some other vaccines and their preventable diseases.

- Polio [8]: During the period of highest infection rates in the U.S., an average of 35,000 cases of polio were reported per year. In 1954, the last year before the vaccine was introduced, this represents 0.02% of the U.S. population [9]. Of that infected population, 72% have no symptom but spread the virus; 24% exhibit minor infection-related symptoms, such as fever, upset stomach, or flu-like symptoms, but do not develop paralysis; only 1% of infected people develop the iconic paralysis that put fear into the nation. If polio-induced paralysis is the symptom that was most feared, and thus the thing most worth preventing when requiring vaccination, then we are talking about 1% of 0.08% of the population, or 0.0008% of the population that was most seriously affected. Was polio worth preventing with a potentially risky vaccine just to save 0.0008% of the population from paralysis? The answer is an unequivocal “yes.”

- Pertussis (whooping cough) [10]: From 1940-1945, there were about 1 million reported cases of whooping cough. This is an average of 200,000 cases per year. This is 0.14% of the population in 1945. Of those infected by whooping cough, the mortality rate in the 1940s was about 0.0025% [11]. The vaccine was introduced to prevent the disease in a significant fraction of the population (certainly a very significant fraction of infants, as most risk for mortality from the disease), and to save the lives of just 0.0000035% of the population who would otherwise die from the disease.

These are just a few examples. We see that due to the nature of the death, or the severity of the disease, or the communicable nature of a disease, we have acted as a people to develop and distribute vaccination for diseases that kill far fewer people than are killed by cervical cancer.

But it is not enough to discuss the incidence or mortality rates of a disease; we should also consider the complications associated with giving the vaccine to the population. For instance, what are the risks associated with giving every woman in the U.S., 12 years or older, the currently available vaccines for HPV? As part of the evaluation of the drug Gardasil, data were collected using a randomized double-blind study of patients [14]. The findings were obtains from 277 women receiving the actual drug and 275 receiving placebo preparations; the groups were randomly determined. No life-threatening or quality-of-life altering side-effects were reported in either group. Standard injection related effects were reported in both groups. For instance, 83% of patients receiving the actual drug reported ” erythema, pain, and swelling, with severe intensity” [14] while 73.4% of placebo recipients reported the same effects. The margin of error on these numbers is +/- 2.7% and +/- 3.6%, respectively (I computed my own binomial errors on these numbers using the numbers presented in the references). These two numbers agree within 2.1 standard deviations, which is not a significant difference between the two groups. Most vaccines yield some kind of injection site effect, and here we see that the placebo causes just as many as the drug.

The CDC information site on the vaccine notes that the medical community continues to monitor the women who receive the vaccine for evidence of very rare complications that won’t show up in such trials. But the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement following Bachmann’s interview on the “Today Show” stating that her comments were irresponsible and fly in the face of any actual medical and scientific evidence about complications associated with the vaccine [15]. They state that 35 million doses have been administered with no scientifically demonstrated causal link to serious side effects.

Let’s take stock of what we have learned. Primary evidence gathered in randomized, double-blind trials shows that one of the two approved vaccines for HPV, Gardasil, is not only efficacious (90% success rate in preventing infection by HPV) but safe (no significant difference between placebo and the vaccine in studies of side effects). There is no additional data that clearly links rarer complications to the specific vaccine. The risk associated with taking the vaccine is small (35 million vaccinations given with no evidence of serious side effects, suggesting a life-altering complication probability of <0.000003%) compared to the fact that death from cervical cancer results in 0.001% of the population.

Bachmann offered only an anecdote as evidence of the need to proceed cautiously with policy regarding HPV vaccination. Anecdotes are a form of eye-witness testimony, and thus unacceptable as primary scientific evidence due to well-documented problems with this form of evidence. Since then, she has reportedly been offered thousands of dollars to produce primary scientific evidence backing up her claim (in the form of wagers from medical researchers) [16]. So far, her campaign has not responded.

We have an excellent teachable moment here. If you want to win the war with facts, you need to provide them. Testimony are insufficient as facts. Anecdotes, then, are anecdon’ts when it comes to making a solid argument.

Footnote

Let’s step away from the science issue for a second and think about the policy issue. Whether or not to require that 11-12 year-old girls received the HPV vaccine is a policy question. There is a science component to this issue. We need to set aside the values issues for a second (e.g. different people, with different ethical or moral world views, will respond differently to the question of whether or not a young woman should receive a vaccine for a sexually transmitted disease, independent of what the science says).

The recommendation about the age of vaccination stems from a couple of pieces of data: how many vaccinations are needed to receive complete protection and when a young woman typically becomes sexually active. The CDC has statistics on sexual activity [17]. For instance, by age 15 about 8% of women engage in oral intercourse and 26% of women engage in vaginal intercourse; rates are similar for young men. At age 14, 5.7% of young women claim to have had sex. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation [18], the median age at which first experience with sexual intercourse occurs is about age 16; that means 50% of young girls have their first sexual intercourse BEFORE age 16. If prevention is the goal, the vaccine has to be administered at an age before which the majority of sexual activity occurs.

Perry’s executive order followed the recommendations of the CDC: begin the vaccination process at age 12 because it takes about 1 year to receive all three recommended vaccinations. That means full protection from HPV occurs at around age 13. That assures that young girls are protected against HPV by the time they become sexually active.

That’s the science that informs the policy discussion.

[1] http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anecdote

[2] The Problem With Eyewitness Testimony from Stanford Journal of Legal Studies

[3] http://archives.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1109/12/se.06.html

[4] “In Texas, Perry’s Vaccine Mandate Provoked Anger,” National Public Radio, “All Things Considered,” http://www.npr.org/2011/09/16/140530716/in-texas-perrys-vaccine-mandate-provoked-anger

[5] “The Today Show,” September 13, 2011. http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/41521818/#44499076

[6] “Epidemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with Cervical Cancer”, N Engl J Med 2003; 348:518-527February 6, 2003. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa021641

[7] CDC, “Cervical Cancer Statistics.” http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/statistics/

[8] CDC, “Polio Disease – Questions and Answers.” http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/polio/dis-faqs.htm

[9] http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/popclockest.txt

[10] http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/pertussis/default.htm

[11] http://www.healthsentinel.com/joomla/images/stories/graphs/us-deaths-1900-1940.jpg

[12] CDC. “HPV Vaccine Safety.” http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/vaccinesafety.html

[13] Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol 2005; 6:271–278. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15863374

[14] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/canjclin.57.1.7/full

[15] http://www.aap.org/advocacy/releases/hpv2011.pdf

[16] http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-504763_162-20107489-10391704.html

[17] http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad362.pdf and “Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, 2002” (PDF). Vital and Health Statistics. National Center for Health Statistics. 2002. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

[18] http://www.kff.org/youthhivstds/upload/U-S-Teen-Sexual-Activity-Fact-Sheet.pdf