Four of us stood in the lobby of the La Fonda Hotel. The beautiful space sits just off the main square in Santa Fe. You could almost feel the ghosts of the Manhattan Project walk past as people now sat, perhaps unaware, reading papers, waiting for friends, eating in the restaurant, or drinking in the bar. Here, in this lobby, Dorothy McKibben first spotted J. Robert Oppenheimer at the bar; within moments, he would walk over and hire her on-the-spot for the position of head administrator of the Manhattan Project Office in Santa Fe. Not a 3 minutes walk from this lobby was 109 East Palace, the nondescript and unassuming home of that office. Somewhere in this space, but in the distant past, was the voice of Robert Serber joined with other Los Alamos scientists trying to talk loudly and spread the rumor, unsuccessfully, of “electric rockets” in the near-empty hotel bar.

We were here in anticipation of the start the next day of our short course, “The Secret City: Los Alamos and the Atomic Age”. Our students would be people who had elected to participate in the SMU-in-Taos Cultural Institute, a marvelous program that unites alumni, faculty, staff, SMU administration, and others in one place to take short courses in fascinating subjects. These range from golf and wine tasting to presidential history and physics. Here, I recollect some of the three days in which I had the privilege to participate and interact with an incredibly engaged audience.

A Trip to Los Alamos

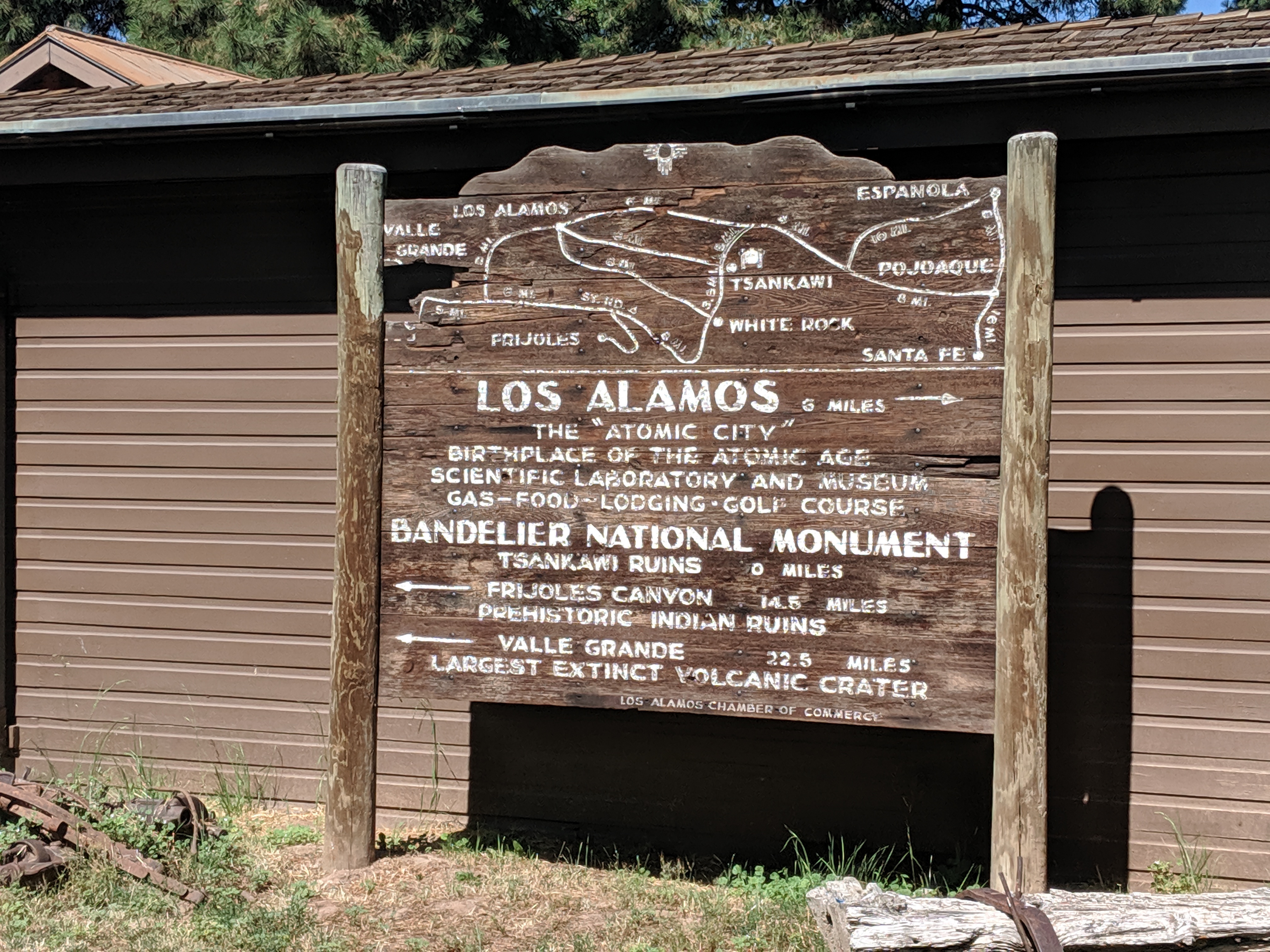

The course began with a day trip to Los Alamos. There, we were treated to a short walking tour of historic sites that remain from not only the Pueblo era of the Pajarito Plateau (the mesa on which Los Alamos is built), but from the era of the Manhattan Project to crash-build the world’s first atomic weapons. I had never been to Los Alamos before, and it defied my expectations.

Driving into the city, you suddenly realize this is a bustling modern city whose residents primarily work at the laboratory and who, over decades of settlement and growth, have evolved this place into the kind of American city you would find just about anywhere. Of course, it has its unique features – for example, the Bradbury Museum and the Los Alamos History Museum that each tell parts of the story of the mesa from the 1900s onward. But there is also a concert stand next to Ashley Pond; there is at least one Starbucks; there are lots of stores, demand for limited numbers of homes, green grass and trees.

I was half-expecting to find a wide plateau covered in scrub grass, ringed by a fence, and painted with derelict pop-up army buildings from the 1940s. What I found was the remaining heart of the original Los Alamos Ranch Boys School and the Manhattan Project-era Los Alamos Laboratory encircled by modern Los Alamos and set off from where the modern and much larger Los Alamos National Laboratory actually sits. The main gate that once marked the edge of security protocols for the mesa is marked now only by the remaining guard tower next to the road on the way into the city.

We enjoyed docent-led walking tours of Bathtub Row (some of the original houses occupied by project leaders, so-named because they were the only houses with bathtubs, which required war-precious iron to construct). We saw Oppenheimer’s house, though only distantly; it is still a private residence and not part of any actual tours. However, we also saw Hans Bethe’s House, which is owned by the museum and can be toured on foot.

This was a chance to immerse ourselves and our participants in history. We lunched in Fuller Lodge, a key building left over from the “Ranch School” era of the Pajarito Plateau. Here, young men were once hardened in wilderness life while immersed in some of the best schooling money could buy. Later, it became a central feature of life in the Los Alamos Laboratory during the Manhattan Project era. Now, it is a building that served history and the public needs of Los Alamos, the city. We were treated to lunch in the lodge and a talk by a recent CTO of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. He gave a great overview of the interface of technology and public/private sector interactions, as well as science in service of security. He also took a lot of questions from the audience, which was fully engaged for this entire event (despite the long bus ride from Taos and the walking on a growingly hot day on the mesa).

The Science of Nuclear Verification

There were three instructors for this course: Cas Milner, nuclear and particle physicist and adjunct at SMU; Jodi Cooley, astroparticle physicist and dark matter hunter; and me, a collider particle physicist. Each of us had a piece of the story after Los Alamos to offer our audience.

Cas focused on nuclear verification, both for countries engaged in treaties and those not bound by them at all. The audience seemed most engaged in the discussion of how the U.S. long history with testing atomic weapons and building platforms for atomic energy enables us to “see ahead” of what other countries with atomic power might try to do. The physics, for instance, of the transmutation of uranium to plutonium for the purpose of isolating plutonium for weapons production has a very definite time structure. Taking the uranium fuel out of a reactor too soon is a clear sign of the use of the reactor for plutonium production, rather than power; this is because leaving the uranium fuel in the reactor longer will “poison” the plutonium with an isotope that is not easily removed. So one can tell if a country is really just generating electricity (they leave the fuel in for a really long time, months or years) or hiding a plutonium production program (they take the fuel out quickly after installing it, so they can quickly chemically separate plutonium from uranium without too much of the “poisoning” isotope being present).

Here, science meets policy. Science enables policymakers to install clear and undeniable verification measures in negotiations. Without these tools, policymakers would have only the “good word” of another country to be sure of their intentions. Instead, seismic observation, fuel cycle observation, physical inspection, and other scientific methodologies provide an independent story about intentions and actions.

A Vision for the Dark Cosmos

Jodi focused on how the Manhattan Project set the stage for the probing of the “dark universe.” For example, physicists who went on to work on atomic weapons testing in the Pacific would include some who would do what was thought to be nearly impossible: detect the neutrino, predicted in the 1930s by Wolfgang Pauli as a “desperate remedy” to solve the puzzles of nuclear beta decay. The co-discoverers of the neutrino, Reines and Cowan, would credit the “no limits” attitude of those atomic weapons tests (money, engineering, and intentions without real limitations) to thinking wildly about how to actually detect the neutrino. They would find their means ultimately in the Savannah River nuclear reactor.

This would set the stage for a suite of tools for detecting very hard-to-observe matter. These days, the focus is on dark matter. Jodi toured the audience through the nuclear physics of neutrino detection and into the material science and solid state physics of trying to detect dark matter.

The Age of Accelerators

I focused on the “Age of Accelerators” that emerged out of the Manhattan Project. Crucial for isotope separation and neutron scattering studies, accelerators were already a vital tool in the Manhattan Project. They returned to the laboratory after the war as a vital tool to answer fundamental questions about the nature of matter and the forces at work in the nucleus. Yes, the nucleus had been “engineered” in the bomb project, but it had not been understood.

I told the story of the birth of this age through the lenses of Isidor Rabi, Eduoardo Amaldi, and Robert Wilson. I set the stage by beginning with the discovery of the Higgs particle and asking my audience, “How did we get to this point where 6000 physicists on two experiments at an international accelerator laboratory are doing large-scale curiosity driven research with no weapons applications?” I pointed to the origins of this at Los Alamos, and in the lives of the few physicists I used as proxies for the larger field in the decades afterward.

A Wonderful Journey

We met many wonderful people during this teaching experience. It was made possible by the excellent staff who paved the way for us for the months beforehand; a special shout-out goes to our course administrator, Marianne, who made everything look easy but who did so by carrying the entire world on her shoulders. Cas, Jodi, and I are indebted to our students, who were so engaged, and to Marianne, who made that engagement possible at all.

I hope we get to do this again. We’ll see how the course reviews go. We already have ideas for how to restructure the course given the new players now involved (Cas, Jodi, and me). It’s a great way to combine physics and desert country… just not in the way Oppenheimer did it.