On Tuesday, February 28, President Donald Trump gave his first address to a bicameral meeting of Congress. While not a “State of the Union” address – a President in office only 5 weeks is in no shape to discuss the state of the union over which they preside – this marks a moment when the President can lay out more specifics about their vision for legislating and leading in the United States. President Trump’s heavily scripted speech, a departure from his more typical off-the-cuff style of speaking, lasted about one hour. I read it with an eye toward focusing on issues related to science and science policy. The speech, in some ways, contrasts with the coming actions on science policy and science funding. While Trump laid out grand themes about the kinds of technology and medicine that might be possible in the future, reflecting on the nation’s first centennial for inspiration, his government’s actions behind-the-scenes and… soon, I expect… in the light of day seem to contrast markedly with that vision. Let’s have a look at some of the contradictions of words and actions, typical of the 6-week-old Trump presidency and the campaign that preceded it, on matters related to science and science policy.

What is Science?

Science is nothing more than a methodology for establishing reliable information about the natural world. A scientist observes a natural phenomenon, proposes a testable and falsifiable explanation for the phenomenon (a “hypothesis”), conducts a test to establish the validity (or not) of the hypothesis (this is called an “experiment”), and reports the results of the experiment with an eye toward whether or not the experiment falsifies the hypothesis. If the hypothesis is falsified, it is to be discarded or, if possible, modified and tested again. If a hypothesis is not falsified, it might be a useful explanation of the phenomenon and lives to be tested another day. The best hypotheses explain existing phenomena while predicting new ones to be searched for in experiments (and, if unobserved, to be used to falsify the original hypothesis).

If a hypothesis survives long enough and is combined with other hypotheses (also successful), it can become a model; if it explains facts, predicts new ones, and continues to yield new knowledge, it might even one day be promoted to a scientific theory or, after a very long time, a law of nature. Scientists have an obligation to share methods and results with the public so that their ideas, if useful, might spread or, at least, be tested for veracity by other scientists.

What is Science Policy?

Science policy is a body of ideas that govern how science is funded or how scientific findings are utilized to make other policy decisions. Because science is a process of establishing reliable information, policy in many areas (health, education, medicine, war, etc.) benefit from the findings of science. Reliable policies, when possible, are to be based on reliable evidence; reliable evidence is established by science.

Science, in the language of economists, is a “non-excludable” good (meaning that members of the public who have not paid for it still have access to it) and also a “non-rival” good (meaning that when one person uses science this does not prevent other people from also using it at the same time). This makes it unattractive to private industry to fund it in today’s fast-paced world driven by short-term gains. One needs funding from agencies with longer-term views. These might be well-funded research and development programs like those embedded in companies like Alphabet (the parent of Google), Space-X, or Texas Instruments. However, the largest source of such long-term funding in the United States is the Federal Government, because it represents a fairly steady and reliable agency that can work with the community to plan ahead for years or decades, depending on the forces acting on or in the government at any one time. Therefore, science policy at the local and national level is crucial to successful scientific enterprises, with research and development cycles that can take decades.

Trump’s Science Vision in Speech to Congress

On Tuesday night, President Trump said this regarding the past and future scientific capability of our country.

On our 100th anniversary in 1876, citizens from across our nation came to Philadelphia to celebrate America’s centennial. At that celebration, the country’s builders and artists and inventors showed off their wonderful creations. Alexander Graham Bell displayed his telephone for the first time. Remington unveiled the first typewriter. An early attempt was made at electric light. Thomas Edison showed an automatic telegraph and an electric pen. Imagine the wonders our country could know in America’s 250th year.

Think of the marvels we could achieve if we simply set free the dreams of our people. Cures to the illnesses that have always plagued us are not too much to hope. American footprints on distant worlds are not too big a dream. Millions lifted from welfare to work is not too much to expect. And streets where mothers are safe from fear — schools where children learn in peace, and jobs where Americans prosper and grow — are not too much to ask.

— President Donald Trump, from Ref [1]

Compared to the grim vision of America presented in his Inauguration Speech [2], this is a downright sunny day on Mercury. There was irony here, however. In a speech that focused, in part, on cutting government regulation and tightening borders, Trump inadvertently defended his vision of American innovation using highlights whose success relied on open borders and the freedom of companies to transgress national boundaries [3].

It’s here where Trump’s grand vision of American innovation collides with his own administration’s anti-free-trade, anti-immigration, and anti-inquiry policies. Science as a successful human enterprise relies on key things upon which the United States has prided itself historically (things upon which it was founded): freedom of movement (the right to cross boundaries within and at the edge of the United States), freedom of commerce (the right to make and move goods across internal borders as well as those at the edges of the nation), and freedom of speech (the right to inquire and to publish, free from the threat of having either taken away from you except in the most extreme cases of demonstrable criminal intent or activity).

Trump’s vision of actual policy, rather than his literary vision expressed in his speech to Congress, is deeply at odds with the scientific renaissance he implies in the excerpt above. It is too much for him to ask for these successes in innovation and science if, at the same time, he restricts the free movement of peoples otherwise authorized to move; if he restricts the free commerce of those who produce or purchase goods; if he restricts freedom of inquiry, deciding who can ask questions and who can print findings.

While so far these restrictions have been tried mainly on refugees and immigrants from just seven nations, on companies that have parts of their business located within the borders of trading partner or other nations, and on journalists seeking to find the truth about claims from and about the new administration, these groups are the most politically vulnerable among us. Americans, like all human beings, tend to have emotional responses, many of them negative, to the idea of immigrants (legal or otherwise) if they represent an “other” or a “different” kind of person; Americans tend to be upset about companies off-shoring jobs; and Americans tend to think of the press as petty when is complains about free access to public figures. However, historically, administrations that seek to restrain the public begin with those most vulnerable or most easily demonized, and then move on to bigger and more well-liked targets.

Americans, as a whole, tend to like science and scientists. See http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/29/public-and-scientists-views-on-science-and-society/

A Real Threat to Science: Funding

If you want to kill a limb, starve it of blood. This is the surest way to kill it. You can poke the limb, you can prod the limb, you can even try to saw it off. But if you want it to die – really die – you starve it of the one thing without which it cannot live: blood, carrying vital oxygen.

Money is the oxygen of science. It’s fine to speak in grand platitudes about letting Americans dream and hoping innovation stems from those dreams. But dreams cost money, as everyone who’s ever had a dream knows first-hand.

It costs money to pay a student to learn to do research. It costs money to have a research staffer who can actually do all the experimentation. It costs money to provide chemicals, gases, cryogens, tools, and computers for a modern laboratory. For faculty who conduct research, it costs money to buy out teaching duties. For senior scientists at a dedicated non-profit research laboratory, it costs money to afford their skills and retain them against the attractive for-profit firms that can afford to pay far more. That’s the economic reality of science. Scientists can be noble – in fact, scientists, like teachers or doctors or volunteer soldiers and first-responders, are a kind of American nobility where the pay is not equal to the service provided. All of those kinds of expertise are home to underpaid people who know they can make a lot more money plying their skills in an alternative profession; but that’s not the point of their profession. The point is to serve humankind in some fundamental way: by uncovering deep truths about the universe, by teaching the next generation of citizen, by caring for the wounded and curing the sick, by standing in front of the bullet intended for another citizen, or by rushing into a chaotic scene where there are people wounded or threatened and being the shield between the citizen and their impending death. But all of these take money, because in our society it is money that buys a roof, food, transportation, equipment, and education. That money can come from many places – from the self, from others – but it comes from somewhere.

Science relies on funding, and if you starve it of funding you can effectively kill it. Well… sort of. Scientists, like other mobile professionals, can almost always find someone willing to hire them and support their work. Other countries, for instance, might lure scientists away from the U.S. if there is clear evidence of a devaluing the American scientific enterprise. As a recent example, a candidate for President in France (Macron) made overtures to U.S. scientists to migrate there if they feel they are undervalued or discarded by their home nation [4]. As long as freedom of movement is preserved for U.S. citizens, citizen scientists might make homes in other nations – much as many scientists from Germany fled that country in the 1930s ahead of or during academic purges (especially based on religious persecution of those of Jewish heritage or faith), or much as scientists at public institutions in the U.S. during the communist witch hunts of the 1950s fled for private schools where they were not required to take “loyalty oaths.”

The lessons of history are to be well-heeded here: the world needs scientists, and while the U.S. may be home to many of the world’s best scientific institutions and scientists today, starving the limb of American science of the vital blood of research funding will certainly begin the death of the limb, but it may also drive the limb to take up residence elsewhere where there is plenty of financial oxygen left.

The Oxygen Supply

While no formal action has yet been taken by the Trump administration, documents obtained by journalists have shed light on the thought process. These signal the kinds of starvation that Trump and his allies plan for federal science funding agencies. The one clear, public thing that we do know about Trump’s funding plans is his plan to request that the Department of Defense have its budget raised by $54 billion [5]. He has also claimed that he will do this while NOT touching non-discretionary spending such as medicaid, medicare, and social security.

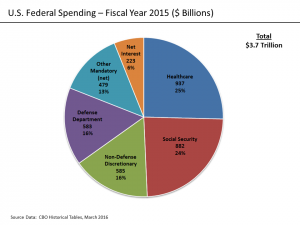

To understand what thus means, we have to take a broad look at the U.S. federal budget. The total U.S. budget in 2015 was $3.7 trillion. Take a moment. Let that sink in.

Now that you’ve had a chance to digest the single large number, let’s break it down into its major pieces. This graphic helps [6]:

There are two major parts to the U.S. federal budget: “discretionary” and “non-discretionary” spending. The former is home to things like science funding and defense spending; the latter is home to things like social security, medicare, and medicaid. Discretionary spending is determined in 12 funding bills initiated in the House of Representatives, developed separately in the Senate, reconciled between the two, and then voted on by the Congress and sent to the President for signature into law. Payments that are mandated by existing law are “non-discretionary,” and must be spent (with legally mandated adjustments… or not) each year. You can see the pressures a Congress is under in a normal budget cycle. They are tremendous.

Non-discretionary spending amounts to about two-thirds of the annual federal budget. Let that sink in. Of the $3.7 trillion spent by the federal government in 2015, about 66% is required spending that the Congress must allocate under laws that cannot be crafted year-by-year. That leaves just about 33% of the $3.7 trillion – about $1.2 trillion – to be spent on everything else that the citizenry deems valuable to society. That includes defense (the military) and then everything else, including science funding.

About half of the purely discretionary spending is on defense. That leaves the remaining money for everything else. So in 2015, the amount of money available for spending on everything else that isn’t mandatory (non-discretionary) spending or defense is about $585 billion.

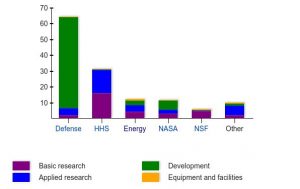

How much does science cost the United States? The total spending on U.S. research and development was about $135 billion in 2015 [7]. However, this includes military research and development, very little of which is basic research (curiosity driven investigations without obvious immediate applications, or research into the development of new medical techniques or technologies). If one focuses just on those (the following chart helps), one finds the number to be much smaller: a mere $35-$40 billion for the whole United States. That amounts to spending just about $100 per U.S. citizen; or, conversely, every U.S. citizen spends $100 each year to fund the entire basic science enterprise of the nation, an enterprise that has delivered fundamental discoveries that made possible mobile communication technology, non-invasive medical imaging technology, industrial quality control processes, and our navigation systems [8], to name a few.

Science provides many economic and non-economic benefits to the U.S. And yet, these benefits are realized by spending only about 1% of our annual budget on basic research. The total amount of money spent on all research and development comes to just 3.6% of the annual budget.

As an aside: If you knew a way to generate more income overall for your household budget by spending a little of your existing income, how much more would you invest at home knowing it would return more in the future, making you, your children and grandchildren happier, healthier, and smarter than they otherwise would be? Would you spend just 1% of your household income? Or more? Or less? That’s a policy question.

In the above, we already see the problem that looms. If the President intends to pit defense spending again all other forms of discretionary spending by raising the defense budget by $54 billion, that means taking an equivalent amount of money out of other non-defense discretionary spending. Since the defense and non-defense discretionary budgets are about equal, a rise of $54 billion for defense (+10%) corresponds to a decline by the same amount in the non-defense discretionary spending (-10%).

How will he take $54 billion out of all that non-defense discretionary spending? There are many ways. He could put the lion’s share of the cuts in a few places. Or, he could spread the cut equally across all areas. Let’s see what the Trump administration might be thinking.

Starving the Limb

Two reports have emerged in the past week, one regarding the science and regulatory agency known as the “Environmental Protection Agency” or EPA, and the other the science agency known as the “National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration” or NOAA.

Regarding the EPA, a draft document suggests that the Administration is planning to recommend 25% cuts to the EPA’s budget [9]. This is clearly in excess of a 10% cut, and represents an asymmetric reduction to this agency compared to others. The EPA’s total annual budget is about $8.2 billion. The proposal targets the elimination of 3000 jobs from the agency. So of the $54 billion in cuts that Trump’s plan would have to achieve in non-defense discretionary spending, cutting the EPA by a quarter and eliminating 3000 people from the agency will provide $2.3 billion. That leaves $51.7 billion to go.

Regarding NOAA, a draft budget memo suggests that the Administration would cut the budget by 17% – again, an asymmetric reduction compared to the average of 10% that would be needed across all non-defense discretionary spending. The total current NOAA budget is about $5.8 billion [11], so cutting by 25% means eliminating about $1.5 billion from this budget. That leaves about $50 billion to go to achieve the $54 billion increase to defense spending.

While slashing these agencies represents a small step on the larger goal toward eliminating $54 billion from the non-defense discretionary spending – remember, we still have $50 billion in reductions to go – they do tremendous damage to the U.S. scientific enterprise. The EPA, in many ways a victim of its own success (clean drinking water and air are far more common in the U.S. than they were in the 1960s and 1970s, in large part thanks to EPA efforts, and so people forget what it was like to have rivers on fire in major U.S. cities and air so thick with pollutants you couldn’t see what lay ahead on the road). NOAA is our eye on the Earth, keeping vigilant watch on how human activity and natural activity is changing the environment and posing threats to U.S. citizens in, for instance, our many coastal communities. These cuts are effectively a strategy to blind the very scientific agencies whose daily task is to keep Americans safe, alive, and alert to the future of the place they call “home.”

A diversion

Let me divert to policy for a moment. There is plenty not to like about these, and many other, agencies. But cutting their oxygen supply is not the way to reform them. Reform takes bi-partisan, bi-cameral, and inter-branch efforts fueled by public input on how science agencies are or are not serving the communities in which they are embedded and with whose interests they are charged. But you don’t reform the local school by cutting its budget and handing that money over to the police (or vice versa). You work together to improve things for students, teachers, and parents. You work together to make communities love their police officers, and to make it possible for police offers serve the communities that they love. Cutting either or both – starving them of the fuel they would need to enact necessary reforms – is not in the public service.

I fear that Trump is trying to pit our military service men and women against the many other servants of this nation: first responders, teachers, doctors, scientists. That is a lose-lose strategy for America.

$50 billion to go

In making what are, ostensibly, political chess moves meant to deliver on campaign promises (increasing the size of the military, cutting funding for agencies that study the climate or enforce environmental policies), Trump and his administration have made a $4 billion papercut in a planned $54 billion dollar wound to the non-defense discretionary budget of the United States. That means there are $50 billion more in damage to be done, and much of it may come down on America’s scientific capability, infrastructure, and personnel. What happens to 3000 EPA staff that would be laid off under Trump’s plan? Nobody knows right now, because there is no plan for them. What happens to researchers who can no longer get grants through NOAA because that grant program is targeted for deep cuts? Do they lose their jobs? Do they leave the U.S.? The climate isn’t going to stop changing because we’re not watching any more. Coastal communities will not be less-drowned because NOAA isn’t reporting on sea level rise or storm surges. Magical thinking will not save our coastal brothers and sisters, not to mention our American siblings in all other places in the United States.

We have to wait and see. But these documents, if applied as formal budget policy in the coming weeks, are a reflection of the darker vision of America that Trump expressed in his inauguration day speech. To make America fail, one need only starve its brain. For this is the organ that Trump and his administration seem to be choosing to deprive of blood.

[1] Trump’s Speech to Congress: Video and Transcript: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/28/us/politics/trump-congress-video-transcript.html?_r=0

[2] Read Donald Trump’s Full Inauguration Speech: http://time.com/4640707/donald-trump-inauguration-speech-transcript/

[3] Trump’s most inspiring story about American innovation depends on the rest of the world: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/03/03/trumps-most-inspiring-story-about-american-innovation-depends-on-the-rest-of-the-world/

[4] Emmanuel Macron enjoins uneasy US scientists: ‘Move to France’: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/04/emmanuel-macron-enjoins-uneasy-us-scientists-move-to-france

[5] Trump, aboard Navy carrier, vows to boost defense spending: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/trump-to-push-pentagon-upgrade-aboard-us-aircraft-carrier/2017/03/02/1577d030-ff26-11e6-9b78-824ccab94435_story.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_federal_budget

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science_policy_of_the_United_States

[8] c.f. “Why Particle Physics Matters” (http://www.symmetrymagazine.org/article/october-2013/why-particle-physics-matters) to understand how just one sub-field of basic research, my own, has made life better for U.S. citizens and people across the globe.

[9] Climate, other programs get deep cuts in EPA budget proposal: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/federal_government/environmental-programs-face-deep-cuts-under-budget-proposal/2017/03/03/34d635d4-0089-11e7-9b78-824ccab94435_story.html

[10] White House proposes steep budget cut to leading climate science agency: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2017/03/03/white-house-proposes-steep-budget-cut-to-leading-climate-science-agency/

[1] NOAA: Our Budget. http://research.noaa.gov/AboutUs/OurBudget.aspx