The end of the second, and all of the third, days of the “Paving the Way to New Discoveries in Particle Physics” conference saw a focus on the strong interaction, machine learning, and deeper dives into fundamental mathematical questions. Also, I finished writing my talk. 🙂

As an experimental physicist at a research laboratory, I don’t get to immerse myself in mathematical physics as much as I could when I was at a university. It’s not that labs are inconsistent with this part of our field; places like SLAC, CERN, and Fermilab all have a history of strong partnerships across mathematics (theory), computation, instrumentation, and experiment. My current home lab is just much less theoretically oriented than many other places, and the neighbouring university eliminated its physics and mathematics departments several years ago1See Flaherty, Colleen. “A University in Tatters“. Inside Higher Ed. April 28, 2021. I will note that the University is now in a period of rebuilding.. I am far from my permanent home institution of Queen’s University, where it would be much more likely to have stimulating conversations steeped in some measure of theoretical physics.

Which brings me to Aspen. The afternoon session on Tuesday, and all of Thursday, saw more and more input from theoretical physics colleagues on the stage. There were some deep dives into quantum entanglement, constraining theory in partnership with the application of machine learning, and expanded or extended theoretical models/frameworks to help us look for patterns of disagreement with the Standard Model of Particle Physics. There were also deeper looks into new ideas, such as approaches that could reveal the Cosmic Neutrino Background, a relic population of neutrinos (56 per centimetre, per mass eigenstate, per helicity mode, throughout the universe) that, if detected, would teach us about the birth of the universe before nucleosynthesis (the formation of hydrogen, helium, and lithium in the first few minutes after the Big Bang).

Personally, I like a deep dive into the guts of modern particle theory: symmetries, gauge groups, transformations, series expansions, loop calculations, etc. I was a “theory minor” in graduate school. The Physics Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison required graduate students to elect a concentration of courses OUTSIDE their intended area of practice. I don’t recall if the department called this a “minor”, but the students certainly did. When I first became interested in physics, I was interested in gravity theory. I became disabused of my skills in theory in the first year of university, and instead discovered an ability for and love of experimental science. But my heart is ever in theory, and I took a theory minor in graduate school as both a personal exploration (a way to force myself to get better at the thing that drew me to the field) and as a thumb in the eye of the universe. I recall electing two semesters of quantum field theory and a semester of string theory as part of that course of study.

So I was particularly transfixed by Nathanial Craig’s talk “New Ideas Paradigms in BSM Physics” (his original title used the word “ideas”, which he struck for “paradigms”). His focus was on recent developments in condensed matter theory, applicable to particle physics. His arguments were aligned along a direction intended to generalize two paradigms, one from Lev Landau and one from Gerard ‘t Hooft, which he summarized as:

- The Landau Paradigm: “The phases of matter are characterized by the symmetries they break”

- The ‘t Hooft Paradigm: “Small parameters are characterized by the symmetries they break”

His argument was that a broader understanding of mathematical symmetry could make the latter hold in particle physics, even though nature seems to be full of violations of the latter concept. I was mesmerized by the arguments that followed, with potential applications to axions, a class of dark matter candidates. There were also implications for magnetic monopoles (charges), long a target of experimental searches, suggesting there are observational features of these particles that might have been overlooked in previous theoretical treatments.

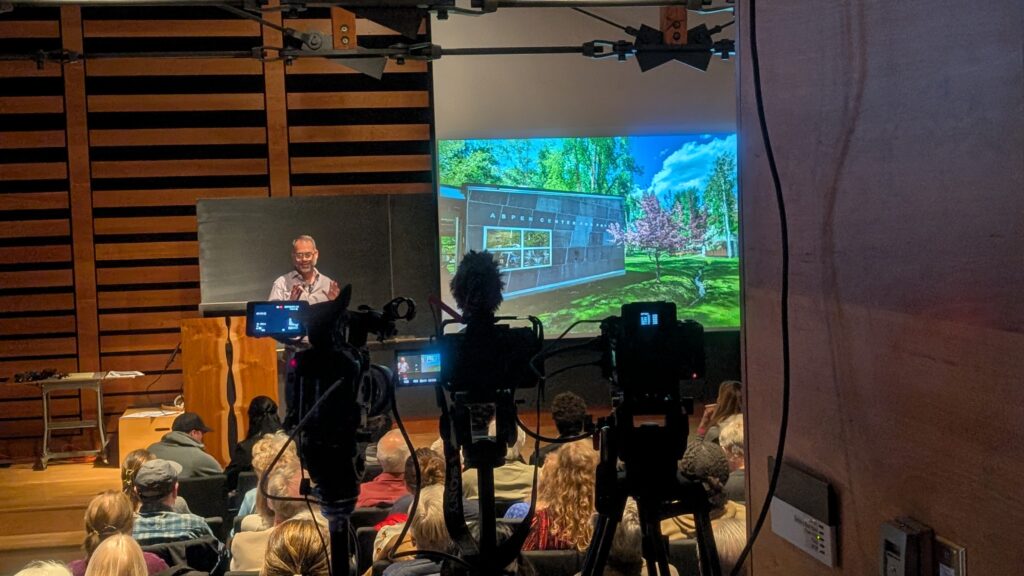

The third day closed with a public lecture by my fellow UW-Madison grad and contemporary student, Kyle Cranmer, who is now the Director of the Data Science Institute at UW-Madison as well as a Professor there. Kyle discussed machine learning and artificial intelligence, what those concepts actually mean, and their benefits, challenges, and implications for science. It was a packed room … and I mean PACKED. Not a seat was free and the public came in droves to see the lecture. The series at the Center is extremely popular and, from chatter around town, beloved.

After the public event, the conference participants went back into the lecture hall to watch an hour of lightning presentation from highly qualified personnel (students and post-docs) sharing their work. This was followed by pizza and a poster session, where the audience could engage with some of the lightning talk speakers in in-depth conversations about their work.