The last two days of the Aspen winter conference on “Paving the Way to New Discoveries in Particle Physics” ended with some pretty interesting stuff. From questions about sources of ultra-high-energy neutrinos to implications for the Standard Model from quantum information theory, this conference did not disappoint.

Getting a Flavour

Thursday’s program began with “flavour physics”, the deep study of quarks and leptons and their relationships in experiment and theory. I cut my teeth in the field on a “heavy flavour” experiment, BaBar, where I wrote my thesis on the search for the rare decay ![]() . That decay links a heavy quark (the bottom quark, part of the B meson system) and the heaviest lepton (the tau lepton, electrically charged senior cousin of the electron). Flavour physics is a mix of precision studies of significant (read: “frequent”) decay processes as well as searches for subtle or rare phenomena.

. That decay links a heavy quark (the bottom quark, part of the B meson system) and the heaviest lepton (the tau lepton, electrically charged senior cousin of the electron). Flavour physics is a mix of precision studies of significant (read: “frequent”) decay processes as well as searches for subtle or rare phenomena.

It was very nice to see many theoretical and experimental efforts in this area. There were some nostalgia moments, too. My Ph.D. thesis subject has continued over the years as a measurement conducted by the BaBar, Belle, and now Belle-II Collaborations. Alan Schwartz (University of Cincinnati) showed the latest measurement of this rare decay process1https://inspirehep.net/literature/2877701, using ![]() of electron-positron collisions. They extract

of electron-positron collisions. They extract ![]() signal events from their data, which can be interpreted as a branching fraction (rate of decay out of all possible B decays) of

signal events from their data, which can be interpreted as a branching fraction (rate of decay out of all possible B decays) of

(1) ![]()

What a JOY to see how far this measurement has come, both with more data and more cleverness than I could ever hope for.

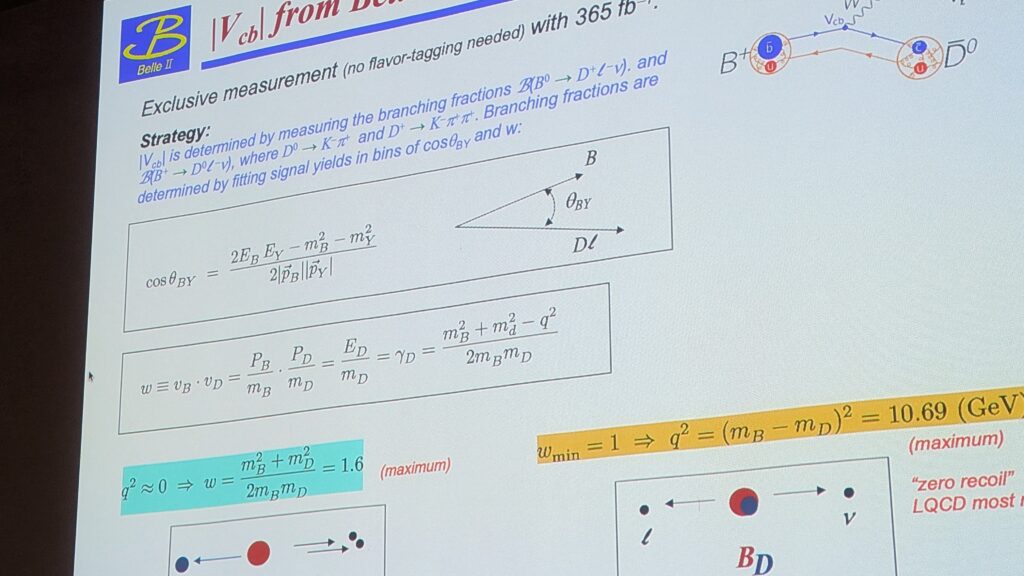

One of the approaches I used in my thesis to constrain the data and reject background contamination was to construct a quantity we called “cosBY”, written more accurately as ![]() . Alan popped this up on a slide at one point, and I was transported back to those early days of the BaBar experiment when a few of us graduate students were using certain B decays to look for rare signatures. This variable was a critical ingredient in those searches.

. Alan popped this up on a slide at one point, and I was transported back to those early days of the BaBar experiment when a few of us graduate students were using certain B decays to look for rare signatures. This variable was a critical ingredient in those searches.

Dark Matter Presentations

I was very glad to give my own presentation on Thursday afternoon, in a really excellent session on dark matter. The speakers complemented each other really well … despite no strong coordination among us, we somehow managed to cover just about every aspect of the field. This was especially true taking into account Wednesday evening’s lightning talks and posters, many of which touched on the axion wave-like dark matter candidate. There were a lot of excellent discussions during the talks and in the hallways afterward, through the next day and into a Friday night dinner.

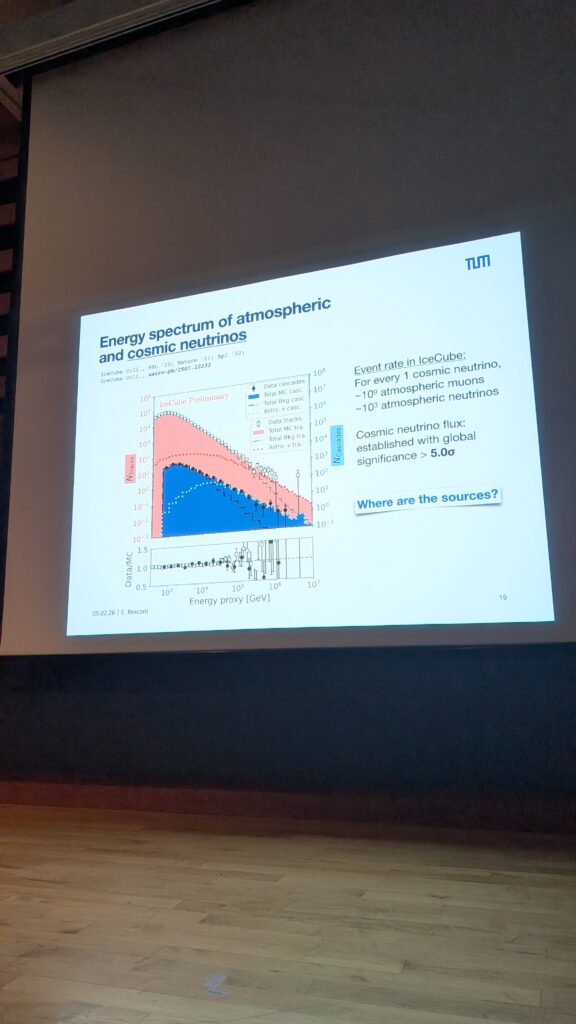

During our session, we were treated to a wonderful talk by Elisa Resconi on the latest updates from the IceCube neutrino telescope at the South Pole. In particular, my attention was caught by the latest results (now more than a year old, but still relevant) on the search for ultra-high-energy neutrinos coming from all directions around the Earth.

I snapped the photo above and sent it to my spouse, whose own Ph.D. thesis back in 2003 was the first search for these neutrinos using the AMANDA-II neutrino telescope, the predecessor to IceCube. How far this has all come as these telescopes have grown bigger and the teams more clever in how they extract science from their observations. It’s quite a thrill to see!

“Quantum Magic”

The conference finished in a strong way with some especially intriguing theoretical perspectives. There were some interested conjectures leading to potential constraints on dark matter (preferring a “warm” dark matter scenario, where the dark matter tends to me moving at intermediate speeds compared to light speed) and on the kinds of symmetry that need to break to help us understand how to resolve some problems in the Standard Model.

A Friday presentation on the application of “Quantum Magic” to the Standard Model was particularly provocative, but in a good way. The speaker has not posted their slides, and I know that they have work-in-progress here. So I will merely cite some of the already published material that was covered in the slides, and give a flavour of where this talk went. If I make mistakes in trying to summarize this, I apologize. I am trying to give a sense of the points, not a monograph for a graduate course.

First, I want to say that the opening half of Ian Low’s talk was one of the most lucid and straight-forward explanations of quantum computation that I have ever seen. I am coming at this from the perspective of a physicist, so that means I am someone who has a comfort zone with the language of quantum mechanics: states, measurements, operators, and linear algebra. Ian did an outstanding job of walking the audience up to the point: a quantum computer is a device that prepares an entangled state and then, to execute a calculation, puts the state through a series of quantum logic gates. The ensemble of outcomes of this process answers the question: what are the results of applying a specific Hamiltonian to a state. The logic gates are composed of matrix operators. For example, the X, Y, and Z gates are the Pauli Spin Operators ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . There is the Hadamard gate, the Phase Gate, and the T gate … all of these composed from matrix operators.

. There is the Hadamard gate, the Phase Gate, and the T gate … all of these composed from matrix operators.

In this way, he built up to his point: really, the universe as we describe it behaves like one giant quantum computation engine. So … what is it computing, and how does it arrive at solutions? The perspective from Low and his co-authors (see References) is this: the universe minimizes or maximizes something.

This is not an alien concept in physics. For example, the second law of thermodynamics notes that a system isolated from external forces (source of energy) will, on average, tend toward a state of maximal entropy. That is, the system tends toward a statistical outcome where the arrangements of things (particles) is the one with the most available ways of being assembled – the state of most “disorder”.

So it’s not a leap to look at quantum mechanics and ask a similar question: are the parameters of the Standard Model set by some process that, in mathematics, one can represent as a maximization or minimization effort?

They consider a process of two particles scattering off one another and construct the initial states as “stabilizer states” of the quantum system. These have “no magic”, to use the jargon from quantum information theory … that is to say, they are states that can be described just as easily using classical physics methods as quantum physics methods. In a quantum computer, a problem that can be solved entirely using states without a physical property that necessitates a quantum description are said to have “no magic”, and thus no efficiency gain in applying a quantum computer instead of a classical one.

The final states, after the scatter, can be thought of as the output of a series of quantum logic gates (operators, representing all the possible scattering processes that take the inputs and convert them into the outputs). So the real question is: what set of solutions is preferred by nature – which we here describe in the language of a quantum computing engine – and is that that preference set by a process akin to maximization or minimization?

What are we to maximize or minimize? Mathematically, one must select a definition and apply it. In this case, the authors chose to apply the Rényi entropy as a measure of magic after the scattering process. High entropy means high magic, meaning a problem that is most efficiently solved by a quantum computing approach … not a classical one.

They then asked: since there are parameters in scattering theory that cannot be determined from first principles, could a maximization of Rényi entropy be related to the observed physical value? For the simple case they considered – the Weak Mixing Angle, or Weinberg Angle, a free parameter of the Standard Model – they found an interesting coincidence. The Rényi entropy of this scattering problem is maximized when ![]() is set to be very close to its accepted, measured value.

is set to be very close to its accepted, measured value.

Other authors have done similar work and found, in Electroweak Theory (a part of the Standard Model), that the Higgs mass as observed is also close to the value that maximized a quantity they referred to as “Entanglement entropy” – another measure of entropy in this quantum information sense. (again, see References below)

It’s too early to know if this is an accident, or perhaps a mathematical ouroboros of some kind. More work by more people is needed here before one gets too excited. But these are intriguing hints of, perhaps, a deeper framework that may help us understand where unspecified parameters in physical quantum theory arise.

Perhaps, dear Albert, God not only plays dice…

… he likes to party while he’s gambling.

This was one heck of a conference.

Reflections on the cosmos

I am very grateful not only to the conference organizers, but to the staff of the Aspen Center for Physics. They helped to connect me to one of my professors from UW-Madison who lives in Aspen. They gave me a tour of all the buildings on campus so I could better understand how the site is used in the summer conferences, which seem to attract more people for longer stays.

I was also very grateful for the people of Aspen. Every Aspen resident I met was kind, helpful, and happy to chat. I met some great people while I was there.

I am also grateful for the beauty of Colorado and the area around Aspen. A bunch of us stayed throgh Friday, into Saturday. The kind organizers setup one more ad hoc dinner for all of us. On my walk on Friday night from my hotel to the dinner venue I photographed the night sky one more time. Physicists are often maligned as people who walk around staring at the ground. I feel like physicists are among some of the few types of humans left on the planet who are always looking up.

Thank you, Aspen, for giving me a lot of chances to look up.

References

A Quantum Computational Determination of the Weak Mixing Angle in the Standard Model

Qiaofeng Liu (Northwestern U.), Ian Low (Northwestern U. and Argonne), Zhewei Yin (Northwestern U.)

e-Print: 2509.18251 [hep-ph]

Parameter Inference from Final-State Entanglement in Higgs Decays

Jia Liu (Peking U., SKLNPT and Peking U., CHEP), Masanori Tanaka (Peking U., CHEP), Xiao-Ping Wang (Sci. Tech. U., Beijing), Jing-Jun Zhang (Peking U., SKLNPT), Zifan Zheng (Peking U., SKLNPT)

e-Print: 2511.17321 [hep-ph]